A breath of fresh air on campus

Sustainable solutions do exist to combat the heat-island effect and keep the city liveable in the future. The horseshoe-shaped VUB/ULB campus immediately catches the eye.

With its trees, shrubs, pond and wadis, the campus literally cools down the densely built-up urban environment. Architectural interventions such as the installation of balcony, roof and wall gardens can also provide relief. In addition, replacing paving with green surfaces is an important step: the less urban space is built up, the less heat can be absorbed. And why not reopen the many streams and brooks that have been paved over in Brussels? So we can splash around on hot summer days!

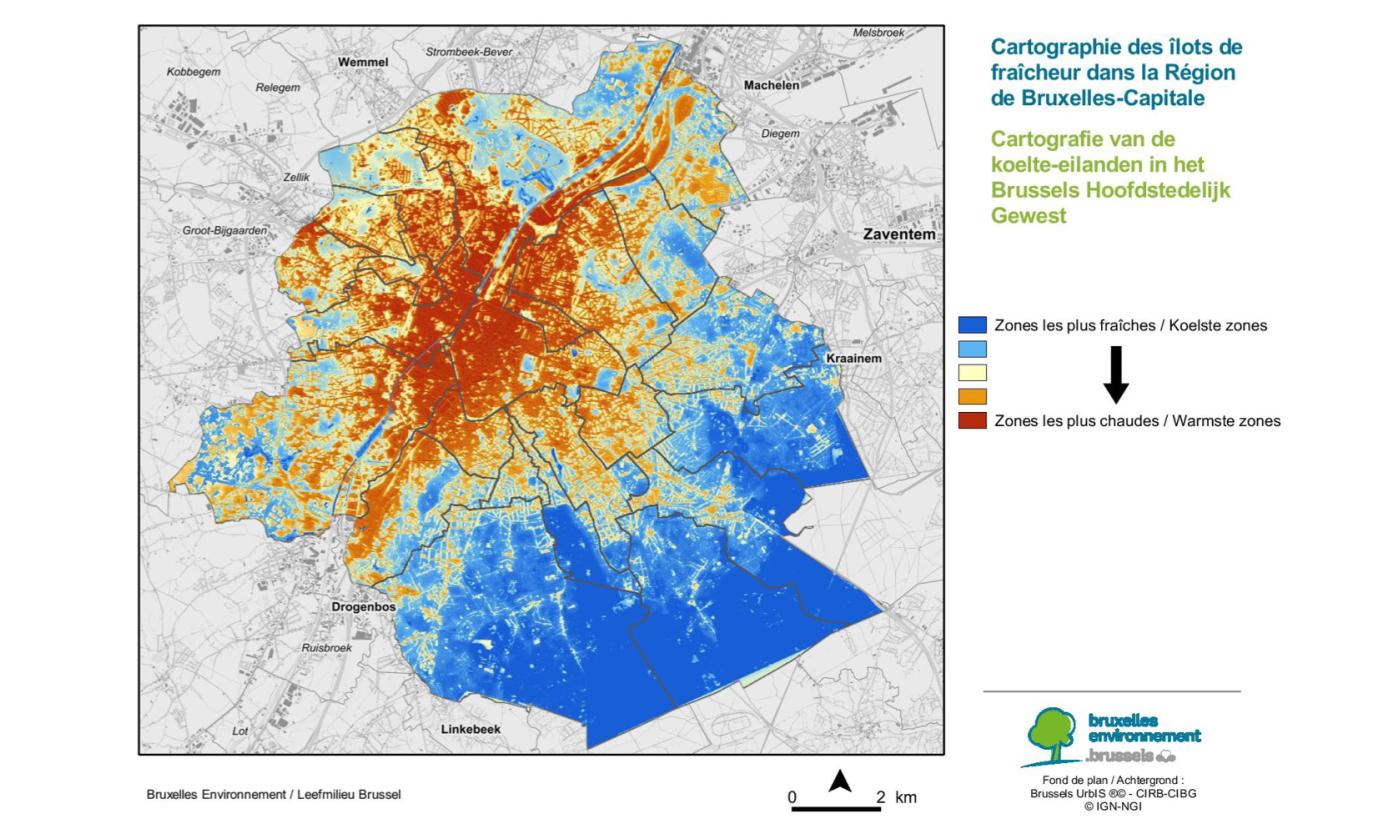

Heat map of the Brussels-Capital Region shows the cooling effect of the VUB/ULB-campus. Source: Brussel Leefmilieu.

What is the urban heat-island effect (UHI)?

The urban heat-island effect leads to a difference of about 5°C on average, but on dry, windless days with lots of sunshine, it can easily reach 8 to 9°C! The intensity of the UHI is influenced by many different elements, including the local climate. An important factor is the material used to build the city: concrete, steel and stone absorb a lot of heat from the sun on summer days. At night, this heat is slowly dissipated again, causing the surroundings to cool down more slowly. Added to this is the heat released by air conditioning, industrial activity and motorised transport.

Health risks and inequalities

The heat-island effect not only causes sleepless nights, but poses serious health risks, especially for children and the elderly. The map below also shows that not all parts of the city are equally affected. The centre and the north western part of Brussels are coloured deep red. It is no coincidence that these are the parts of the city with the densest development and the least green space. The UHI therefore creates serious inequalities: groups with a lower socio-economic profile that live in the dense inner city are harder hit. Moreover, they have access to fewer public parks to cool down. Climate change will only exacerbate these problems, with intense periods of prolonged heat.