Femke Lakerveld, a Dutch actress and chair of the Vrij Links movement, is a staunch advocate for artistic freedom, a secular society and the revaluation of individual liberty. The VUB is recognising these values at its Feest van de Vrije Geest (Celebration of the Open Mind), where both Lakerveld and Guy Mortier will receive honorary doctorates.

What do free thought and artistic freedom mean to you?

Femke Lakerveld: “A free mind is autonomous and unafraid. In the arts, one might say it means staying true to your artistic vision, even if it threatens your career. That’s the short answer. More broadly, a free mind means someone who looks beyond prevailing morals, conventions and ideological or political frameworks. It’s someone who walks their own path despite pressure from society, family or an oppressive regime. In this sense, free thinkers – akin to what the VUB stands for – are independent of orthodoxy and dogma. Perhaps in academia, it’s the students and researchers who are quiet for the longest but dare to question the most. They’re not searching for confirmation of their beliefs, but for refutation.”

“Even without money, power or status, you should still have the chance to make your voice heard”

How do you embody these values in your work?

“To be clear, I don’t see myself as an activist – at most, I’m someone who follows her own path as an actress, creator and chair of Vrij Links. I’m not famous or notorious enough to attract the attention of aggressors, I’m not ostracised by my family, and I’m certainly not Theo van Gogh or a free Iranian woman letting her hair blow in the wind. But I do challenge myself to remain open and true to my values, even when it gets tough. I try to recognise aspects of free thinking and give them space in my own work and that of other artists through Vrij Links, by initiating projects that prioritise free art rather than the outcomes desired by cultural policymakers. I see artistic freedom and freedom of expression as fundamental rights. Even without money, power or status, you should still have the chance to make your voice heard – that’s the driving force behind a free society.”

Did your background hinder or encourage you to think critically and express yourself freely?

“Free thinking is not a luxury, but it is precious. The price can be high, from losing your job or livelihood to living with threats. I come from a small family; I was raised by my mother. When I was five, she went to art school, something her parents hadn’t allowed her to do. She made life choices against the grain, and in that sense, she showed me how to maintain autonomy and stand firm under pressure. We weren’t well-off, but she always took me to museums and theatre performances and found the best school nearby that I could just about cycle to on my own. I studied social sciences at Utrecht University in the 1990s, a time when critical thinking was paramount. Several significant setbacks in my health [she was diagnosed with long Covid] have hindered my development and freedom, but this has also strengthened my mission. Being able to participate in debates without being penalised for it, good health and financial independence – these are not a given for many people. As a society, we lose our moral foundation if we no longer wish to see or hear the most vulnerable among us.”

Who or what has been a role model or source of inspiration for you in terms of freedom of expression?

“I think of someone like [French-Moroccan atheist, feminist and former Charlie Hebdo journalist] Zineb El Rhazoui. She says plenty I don’t agree with, but I greatly admire her for continuing to fight for human rights, gender equality and journalistic freedom despite continuing threats and violence. Culturally, I find inspiration in British satire, like Jonathan Pie and Philomena Cunk. In the Netherlands, we have some excellent cartoonists, including Ruben Oppenheimer, who persists despite significant external pressure. And the young [Turkish-Dutch] author Lale Gül, for her courage to stand up for freedom of conscience and the importance of secularism. Lastly, Eddy Terstall, a director I’ve worked with and a good friend. His liberal films are particularly inspiring to act in. We’ve travelled together a lot, even to countries where freedoms are scarce. These experiences laid the groundwork for the founding of Vrij Links six years ago.”

“Bad ideas should be countered with better ideas”

Should we be able to say anything on stage or in the media? Are there limits to freedom? Where do you draw the line?

“We must always be able to criticise power and authority. And you should be able to make jokes about anything. The courts decide the boundaries. In the satire I create, I certainly can’t afford to shy away from taboo topics. That’s simply not possible, especially with political satire. It’s fascinating to see how differently people interpret my work. Some are outraged by a minor phrase rather than the injustice being highlighted. I personally have a great affinity with equal opportunity offenders – those who don’t spare any ideological or political side in the debate.”

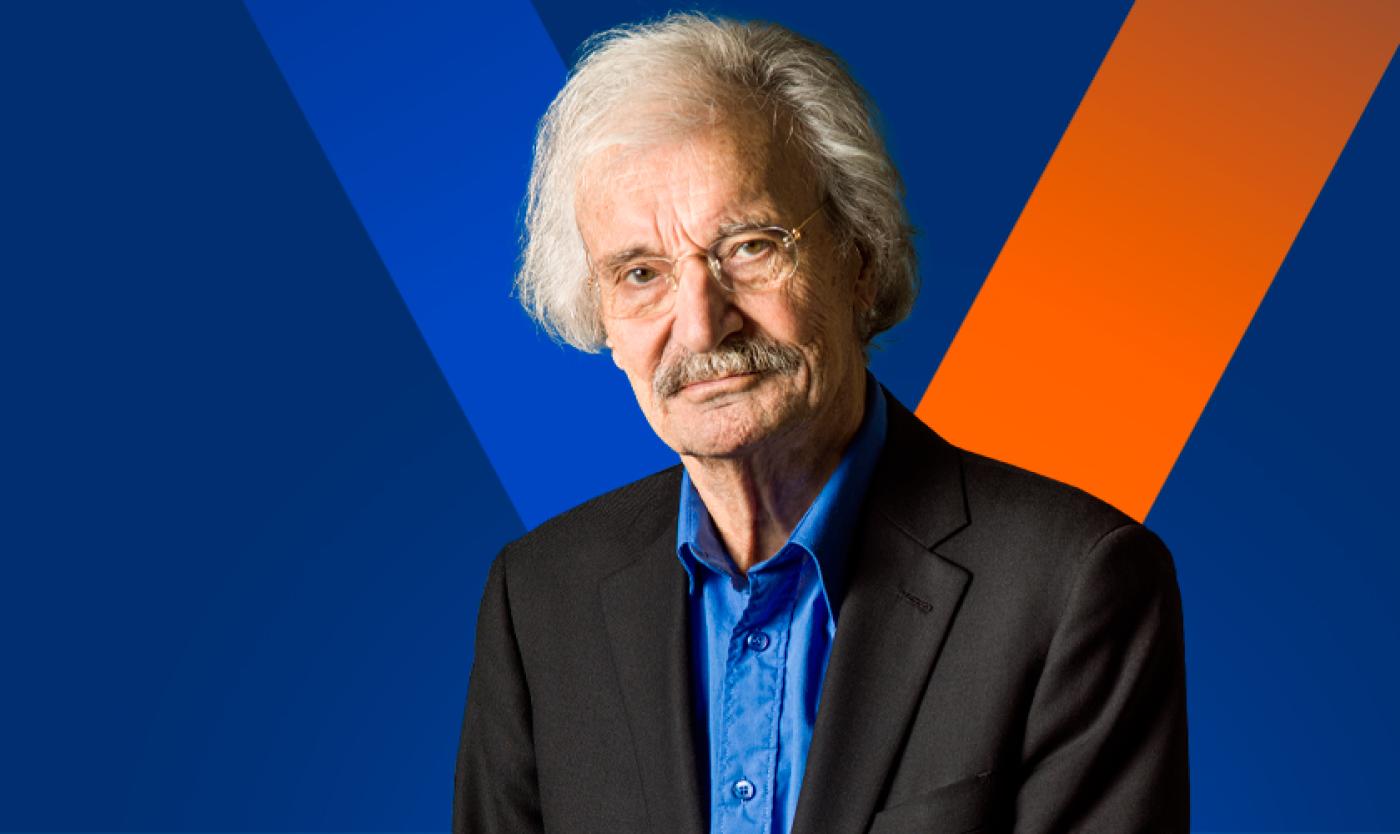

Photo: Roeltje van de Sande Bakhuijzen

How tolerant are you yourself? Would you ‘cancel’ someone?

“Of course, there are things that make me angry or that I’d rather not listen to, from racist drivel to conspiracy theories. Moral superiority makes me uneasy. But instead of avoiding or cancelling those topics, I’d sooner make a video about them. Bad ideas should be countered with better ideas. And you always have the right not to watch. The moment you start limiting the space for artists by censoring or sanitising their work, it says more about the decreasing resilience of the society in which this happens. My view, and that of Vrij Links, is that people have rights, ideas do not. Even in my own work, I can be tough on ideas, but it’s never my intention to tear people down. One of the hardest things is to challenge your own dogmas so that you can change your mind. You have to periodically scrutinise your own thinking; otherwise, you become stuck in your ways. I always have the optimistic hope of encountering this in public debate, sometimes against my better judgment. In other words, I support more voices, more perspectives, rather than removing them from the debate. It’s only when I cannot yet distance myself from something or think of jokes about it that I will sometimes avoid a topic. I’m thinking in particular of the issues in Dutch youth care, the rise of antisemitism and the political disinterest in chronic illness.”

“Wherever dissent is excluded, stagnation lurks”

Do you think someone should be able to demand, on religious grounds, that certain things shouldn’t be said?

“No, absolutely not. Again, under the motto: people have rights, ideas do not. Religion is also a man-made idea and therefore should not be above criticism. Moreover, I find it problematic that many progressives are hesitant to criticise the orthodox, misogynistic and homophobic excesses of religion. They should consistently and uncompromisingly stand for progressive values like human rights and equality.”

How much is freedom of expression under threat today? What do you see as the biggest threat?

“Fundamentalist and dogmatic rules, from any ideological, religious or political corner. What doesn’t help is that ‘no debate’, the exclusion of certain topics from discussion, has become an acceptable strategy. The goals have shifted from becoming resilient to preventing people from being hurt. By excluding certain ways of thinking, a monoculture quickly arises. I see this happening in the Dutch cultural sector, which often dictates moral frameworks, or who is allowed to create something and who is not. This risks turning cultural institutions into the least creative places. You can draw a parallel with academia and the pressure on free research. Wherever dissent is excluded, stagnation lurks.”

Do you see any positive initiatives, anything that gives you hope?

“Fortunately, there are always contrarian types. I can’t help but think there are quite a few at the VUB as well. People who dare to question prevailing norms, create beautiful things and surprise us. The intolerant part of society, both on the left and the right, is often loud but also relatively small. My hope lies with the reasonable majority, who have no interest in polarisation or easy answers to complex questions. Through my work, I meet so many people from various backgrounds and political leanings who help amplify the progressive and liberal voice. My 18-year-old daughter and her peers are engaged and easily translate their involvement into action. Common sense, level-headedness and humour can be found across generations and groups, and they are the antidote to polarisation and intolerance.”

Finally, how can we sharpen our own free minds?

“Anyone who knows that, please tell me... Perhaps by not being afraid of dissent. By questioning things out loud more often. By creating space for experimentation and failure. But perhaps there’s an even greater challenge first – by embracing self-mockery and self-reflection. Your laugh always goes to your gut first, and then to your head. Your laugh is a perfect indicator of how you really feel about something, what truly affects you. And that always crosses the boundaries of what you intellectually consider possible. If you do feel angry or offended, consider that it’s a small price to pay for a life in a free democracy.”

Bio Femke Lakerveld

Femke Lakerveld is a Dutch actress and the chair of Vrij Links, an independent social movement committed to free and unrestricted debate, a secular and solidaristic society and the revaluation of individual freedom.

She regularly publishes on art, culture and social issues. Currently, Femke features in Alles Flex, a youth series by Dutch public broadcaster KRO/NCRV. She is also making waves online with satirical videos as the fictional politician Mira Ornstein and producing a short film about free art.