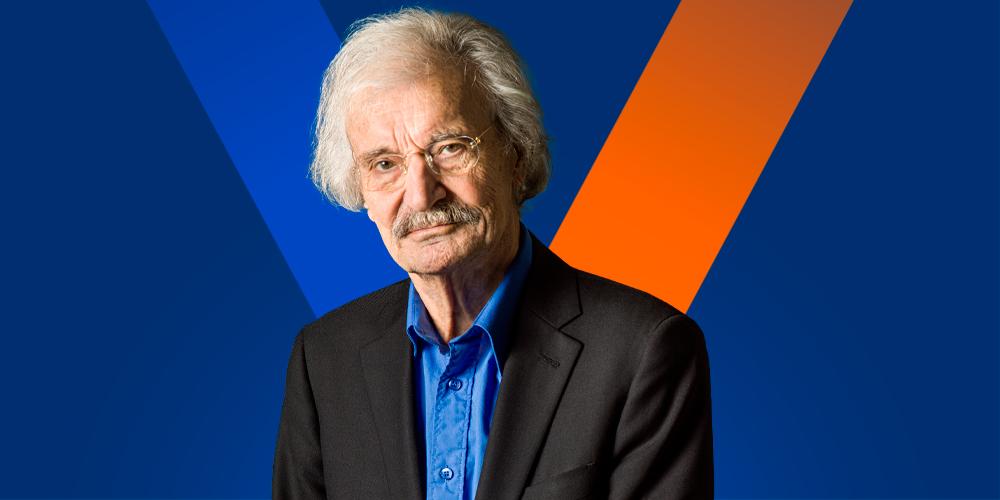

On Friday 20 September, the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) will confer an honorary doctorate upon Guy Mortier, the man who left an indelible mark on the Flemish press, politics and society as the long-time editor-in-chief of Humo magazine. He approaches the event at the Koninklijk Circus in Brussels with mixed feelings: “I was happy with the award, and grateful. Until I realised that it meant a speech. And an interview. Since then, my enthusiasm has cooled somewhat.”

We meet on the terrace of Café Gitanes in Antwerp’s Zurenborg district, a few hours before it opens. Guy Mortier is a regular here (“Great music”). The interview starts off a bit awkwardly. Mortier has a reputation for being somewhat reserved (“Could be”), avoids the limelight (“Not really into it, no”), and feels no compulsion to share his opinions on every matter with the world (“Do you?”). Let’s hope for the best.

What went through your mind when VUB called? Did you hesitate to accept the award?

Guy Mortier: “You’d have to be a dog to refuse an honorary doctorate. But as luck would have it (laughs)… no, of course, I was pleased and honoured. Especially since I didn’t expect it at all. Exactly 10 years ago, I had a similar surprise when I received the Flemish Culture Prize. That was also a joyful surprise. Deep down, you hope your work is appreciated. I’m already wondering what they’ll come up with in another 10 years.”

Why are you receiving this honorary doctorate?

“Because of societal merits, the text said. Your guess is as good as mine.”

The values of VUB – critical thinking, questioning everything, freedom of expression – do they resonate with you?

“Those are my values, of course. I never framed them within a philosophy like secular humanism or an institution like VUB; I assume they came from my upbringing and what I’ve learned over time, through reading and living. Working for Humo only accelerated and clarified that.”

“Daily early mass at 7am! Jesus, that was tough”

You come from a Catholic family. How did you lose your faith?

“I didn’t really lose it. With your VUB background, you probably think of Saul being struck off his horse by the Lord on the road to Damascus (laughs), but it wasn’t like that. It just faded away at some point. My mother was an extraordinarily kind, gentle woman, deeply religious, and she probably prayed me through a few exams and tough moments because she could. Her parents were Limburg farmers in Berlingen, near Hoepertingen, where I regularly spent summer holidays as a child. When it stormed and thundered outside, I’d sit with my legs pulled up on a chair, listening to the litanies prayed to keep the lightning away, because we were told our feet shouldn’t touch the floor. Practical religion. Covered from both sides."

What about school?

“Daily early mass at 7am! Jesus, that was tough. And every Sunday: early mass, high mass and vespers. I hesitate to admit it – hopefully they won’t revoke my honorary doctorate – but even in my first year at university, I still regularly went to evening mass in a small church. Tiensestraat, I think? For the peace, but also, remembering my mother, to send feverish prayers for success in my exams, and even for FC Beringen, who I fervently supported at the time.”

You prayed, and did God listen?

“Not always, unfortunately. Beringen needed constant miracles, and I couldn’t do everything. But that’s not why I lost my faith. In my first year at university – I was 17 – I didn’t know many people, didn’t go out and studied every day, although I did spend some time on the rock ‘n’ roll programme I was making for the BRT [the precursor to the legendary radio show ‘Schudden voor gebruik’]. In the second year, everything changed: I made friends, discovered the brotherhood of student clubs, the cafés… the zeal for study disappeared. It’s not an inspiring story, but suddenly, my faith was gone too. Almost naturally.”

You started working for the radio as a young student and soon after that you joined Humo. How was that?

“Yes, rock ‘n’ roll was my life, and I loved writing, especially complete nonsense, so it was a great stroke of luck. And then to work for Humo… That had been my dream since childhood because we read Humoradio at home. And Gazet van Antwerpen, which didn’t exactly make you rebellious or cheerful, though I have nothing bad to say about [comic strip] Piet Pienter en Bert Bibber. The other newspapers weren’t much better. But when I became editor-in-chief, information came at me from all sides: suddenly, I learned so much that I had no idea about, because you couldn’t read or hear about it anywhere here.”

In 1969, you became editor-in-chief of Humo. Were you already thinking ‘I want to change the world with this magazine’?

“Of course not! I just wanted to make the best possible magazine, with strong stories, sharp interviews, swinging pieces and a solid pop section. And humour! That commitment only crept in gradually. I remember it well: the first ‘heavy’ series I ran was about the many US-installed dictatorships in Latin America and the inhumane oppression that followed. It was completely new to me, and I assumed to the readers too.”

The big interviews and investigative reports in Humo have always sat alongside lighter pieces and humorous comics. Why is that?

“That was a conscious choice. I was always careful not to make the magazine too heavy. The ‘harder’ work, let’s say the pieces people didn’t immediately buy Humo for, I initially limited to literally one, then two pages a week, and gradually expanded. Important new information that I felt everyone should read, I often placed in the first half of the magazine, so you’d come across it while flipping through to the more popular interviews and series, which I sometimes placed in the second half. The rhythm was also very important, the alternating of light and heavier pieces… and humour everywhere, of course.”

So you made the magazine you wanted to read yourself, where the greatest sin was dullness?

“Absolutely. It had to swing, it had to be a pleasure to read.”

Humo had a significant impact on other magazines and newspapers. Your approach, from writing style to that mix of seriousness and humour, has been widely copied. Why is that, do you think?

“There’s nothing like the real thing, of course, but it’s true. You can’t compare the general level of newspapers and magazines then to what they are now, but Humo did pave the way. Everything had to be well or brilliantly written. And the best Dutch writers wrote columns for us: Remco Campert, Kees van Kooten, Gerrit Komrij, Jan Mulder… they all wrote for us. That had enormous appeal. Anyone who wanted to write at that time applied to Humo.”

"The editorial team was a young bunch who went at it with sharpened rapiers; we knew better about everything!"

Even small stylistic elements like “(laughs)”, which you started, have been widely adopted.

“(Laughs) Yes, I liked that. I actually remember who came up with what. ‘(Thinks)’, for instance, is from Jan Antonissen. It pops up everywhere too.”

Humo played an important role in the emancipation of Flanders. You’ve touched on many sore points, haven’t you?

“We also had a very big responsibility. In the 80s and 90s, we had an average of 1.3 million readers. One in three Flemings read Humo! It’s almost unimaginable. The enthusiasm – first mainly among students, then the rest followed – was enormous, it pushed us forward. The editorial team was a young bunch who went at it with sharpened rapiers; we knew better about everything! And we wanted a better world! But we evolved too. In those days, some still liked to drop the word ‘revolution’ in their pieces. It sounds tough, but I’ve always been a follower of John Lennon: ‘But when you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out’. We eventually had a meeting about it and stopped. Because what was that revolution? And what came after?”

In other areas, you didn’t hold back. I remember the cover for your first series on the Brabant Killers: a gendarme in a balaclava.

(Raises a finger) “That was me. That photo was taken just around the corner, by Herman Selleslags – he lived two houses away. The night before that issue came out, I was trembling in bed. I thought: have I gone too far? They really know where I live. But it was a good cover, for a groundbreaking series. Whatever we published, the goal was always to tell the truth, and that led to great anger more than once, including in government circles and at the BRT.”

How did the powers that be react?

“What could they do? At one point, CVP ministers were banned by their party leadership from giving interviews to Humo. We’d been too critical of the party. But that didn’t last long. We didn’t care, and they were cutting off their nose to spite their face and soon came back. Wilfried Martens told me much later: even when he had been prime minister many times, he had no idea what Humo actually was and represented; he only realised much later how many people he could reach through us. Leo Tindemans was always terribly difficult. He had a huge dislike for Humo and refused every interview request. Just before the 1979 European elections, he suddenly allowed us an interview. Jean-Pierre Van Rossem, an excellent interviewer, made a very good article out of it, which was so extensive that I published it in two parts – but after the elections (laughs heartily). He didn’t need it, as it turned out, because he got over 900,000 votes.”

Humo’s rebellious years also met with a lot of resistance from the publisher, didn’t they?

“Fortunately, our publisher, the Dupuis family, was French-speaking; they simply couldn’t read Humo. Except for one brother-in-law, René Matthews, who regularly flew into a rage over what he read and vehemently opposed our progressive line. I often had to go to headquarters in Marcinelle to get a dressing-down. Matthews usually wrote his edicts in pencil on the back of used envelopes – they were notoriously frugal there – and at one point we were forbidden ever to mention the name Gerard Reve again, because of the Donkey Trial [a blasphemy trial against the author]. Behind our backs, he even regularly altered texts that displeased him, which we only noticed when Humo was printed, and even images: on a photo in the TTT pages of Paul McCartney with his baby daughter, they’d placed a black bar over her bare belly – those were the days.”

Yet Humo was a cash cow for them.

“Oh yes! The millions were rolling in, and despite all the threats and grumbling about godlessness and leftist agitation, their wallet always came before their religious principles. The circulation kept rising, and the ad pages kept pouring in! At one point, I even had to fight for every big piece to open with a double page, which was a minimum – they wanted ads everywhere.”

You were often attacked, but real blood was never shed. After the Charlie Hebdo attack in France in 2015, house cartoonist Kamagurka said he didn’t want to die for a cartoon of Mohammed.

“That attack was horrific, and I understand Kama. You’re dealing with people who are extremely unreasonable: you shouldn’t want to be too brave. Not that it excuses anything, but I have to say: in my relentless, often desperate worldwide search for funny cartoons and strips, I never found anything in Charlie Hebdo that I thought was suitable or just funny enough to put in Humo. Technically virtuosic, but purely aimed at shocking. Where was the humour? But again: you shouldn’t be killed for that. And it had disastrous consequences for free speech outside of that.”

People seem to be more easily offended these days. Are there jokes you wouldn’t publish today?

(Thinks for a long time) “The rule is still: if it’s funny, it should be allowed, but the world has changed, of course. Now, it’s about whether it was funny and could be published when we did it. Humo has always featured many types of drawn humour: Ever Meulen, Kamagurka, Herr Seele, Jeroom, Jonas Geirnaert, Hugo Matthysen, Peter van Straaten, Gummbah, and I’m forgetting some – they’re all different, but all top-level. People with talent will always be able to put that across in the right way, I think.”

“I stay away from social media myself; I don’t want to get sick”

Newspaper and magazine circulations are declining year by year. Are we heading towards a world without a critical press?

“That would be a disaster. The world is already at risk of becoming a theme park for conspiracy theorists, liars, fake news spreaders, scammers. Who will still show us the facts and help us frame everything truthfully?”

Young people aren’t used to paying for information. What’s your message to them?

“Find your information from reliable titles; there are so many offers and discounts. Invest in a subscription; it doesn’t have to cost much. Sit in a library and read all the newspapers and magazines from around the world for free! Read books! And in between, watch the news. But now I probably sound as old as I am. Come on, do you really want to rely on something as unreliable as the internet? I stay away from social media myself; I don’t want to get sick. When I see how facts don’t seem to interest so many people anymore… ‘Alternative facts’, the term alone! Trump, the nail in my coffin! I was sooo happy when he lost the last election, and we got a break from his constant presence. That the news and papers reported every tweet from that lunatic and every crazy statement for four years is something I can’t condone. ‘Great content’, yeah right. They really need to reflect on that."

Since you mentioned your coffin: you’re still as sharp as a tack physically and mentally, but do you ever think about the end? Self-determination is another important value at VUB.

“Very little, almost never. But I do know I really need to get my euthanasia papers in order. I know and appreciate [palliative care doctor] Wim Distelmans very much and visited [end-of-life support association] LEIF with my wife a few years ago because I want to have everything arranged. I regularly come across those papers while rummaging in my office, and I think every time: I really need to fill these out. Well, I promise you: I’ll do it this week.”

Do you think you’ll live to see the end of Humo in print?

“What a nasty question. I hope not.”

Long life?

“Or a timely death, of course (laughs).”

Bio Guy Mortier

Guy Mortier (Mol, 1943) studied Germanic philology at the KU Leuven. In 1961, he started working as a freelance journalist for Humo.He was editor-in-chief from 1969 to 2003 and, after his retirement, remained creative director until 2010. He developed a range of successful new sections and editorial formats for the magazine and launched many talented young writers and cartoonists. Humo was closely associated with the dual festival Torhout/Werchter (now Rock Werchter), which Mortier presented for 20 years. He initiated events such as Humo’s Rock Rally, Humo’s Pop Poll Avonden and Humo’s Comedy Cup. He became known on radio as a panellist in De Taalstrijd and De Perschefs and on television in Alles kan beter and a segment on De laatste show.