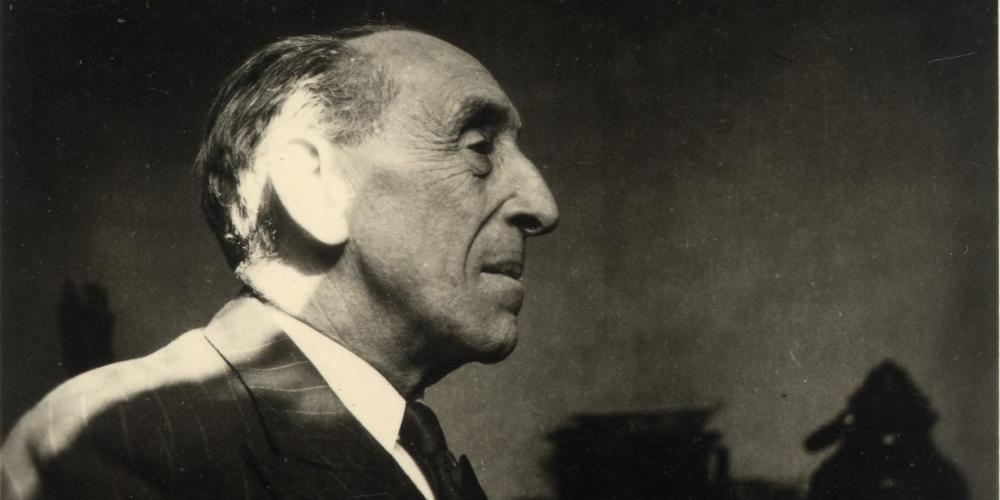

VUB professor of Dutch Literature, Hans Vandevoorde, has penned a biography of August Vermeylen, focusing on his wartime years from 1939 to 1945. Vermeylen, a notable figure as both a committed Flemish activist and Belgian loyalist, was the first to earn a degree in Dutch at the ULB. His philosophy centred on independent thinking and acting in the community's best interest. “Humanism was the foundation of his thought. His ideas on humanity are more relevant than ever in today’s world of conflict. In this sense, and thanks to his role in the ‘Flemishification’ of higher education, the VUB indirectly owes him a great deal.”

Do you consider this biography part of your academic work?

"I do, but I'm not sure if my evaluation committee will agree. I've been told I write too much for popular media. The only thing that seems to count in academia are peer-reviewed international contributions. I wanted to write a book that anyone could enjoy without prior knowledge, yet still be academically sound and reviewed by peers."

What is the focus of your research?

"I work on Dutch literature from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. In 2021-2022, I took a sabbatical, which I partly used to study the art critiques of Jan Walravens, a Brussels-based critic. This research will culminate in an exhibition at the FelixArt Museum in Drogenbos. Recently, one of my students, Stefan Clappaert, completed a PhD on the art critiques of Hugo Claus, an unknown aspect of the writer."

What makes art critiques so fascinating?

"My PhD was on the poet Karel van de Woestijne, and I noticed that his art critiques were also very lyrical. The tradition of critiques written by authors really interests me. Claus, for example, sought to turn his critiques into literary works that matched the quality of the art he was reviewing. He particularly supported Cobra artists like Corneille, Alechinsky, and Appel."

Hans Vandevoorde

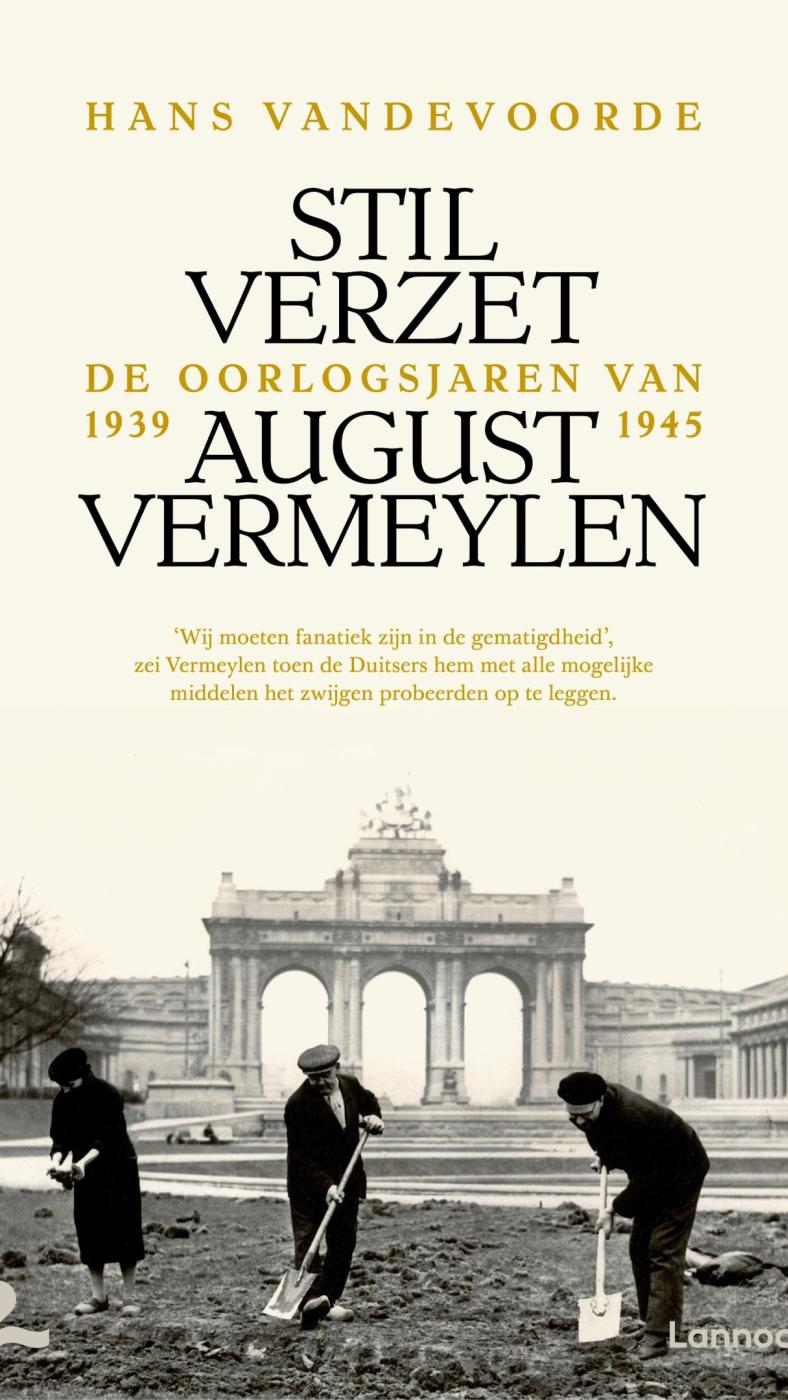

"'We must be fanatical in moderation"

Did you stumble upon Vermeylen during your research?

"After my PhD on Karel van de Woestijne at UGent in 2002, I pursued a postdoc on the literary magazine Van Nu en Straks, which Vermeylen founded in the late 19th century. He wrote sharp, well-formulated essays for this publication. In 1896, he criticised the Flemish movement for focusing solely on language, arguing that it should also address social issues, like improving the working class's well-being. He was an intellectual anarchist at the time but soon converted to socialism, becoming more moderate, a trait that defined him throughout his life. His famous quote on the cover of my book says, 'We must be fanatical in moderation.'"

"Vermeylen was also an art historian. He first studied history at the ULB, where he became the first to earn teaching qualifications in Dutch. Soon after, in the early 20th century, he was appointed at the ULB. However, after WWI, when the French-speaking community retaliated against Flemish activism, Vermeylen was virtually ousted. Students even attacked him in the streets. During this period, he became involved in the movement to 'Flemishify' the University of Ghent, which led to his harassment and eventual move to Ghent in 1923. Seven years later, he became the first rector of the newly Flemish university. In 1921, he was also elected to the Senate, where he didn’t make much of an impact. In his diary, he amusingly recalled someone commenting on his lack of participation in debates, to which he replied, 'How so? Sometimes it says, (Laughter) – that’s me.' He primarily focused on education and culture in Brussels."

"Vermeylen played a significant role in cultural politics. He was one of the first presidents of the PEN Club and the VVL (Flemish Writers' Association). He also founded the Flemish Club in Brussels, which, before WWII, included everyone who was part of the Dutch-speaking cultural and political elite. Today, that club has been hijacked by far-right extremists. In 1940, the German occupiers forced Vermeylen to relinquish all public offices. There were several reasons for this, one being that, like most parliamentarians, he fled to France in 1940. In addition to abandoning his post, he had spoken at several anti-fascist meetings before the war, where he denounced the persecution of Jews."

Yet he didn't abandon his compromised friends and students, did he?

"Take Ernst Claes, for instance. He was a friend of Vermeylen’s but also very pro-German. They were both members of the Mijol Club, an informal Brussels society founded by Herman Teirlinck, where the Flemish elite gathered on Friday evenings. Claes soon realised he was no longer welcome because of his collaboration with the occupiers. Nevertheless, Vermeylen wrote letters in his defence during the period of repression."

Did Vermeylen’s image suffer from the post-war stigma surrounding the Flemish movement?

"Vermeylen wasn’t a Flemish nationalist. He was both a Flemish activist and a Belgian loyalist. He supported a degree of cultural autonomy but not the splitting of Belgium. He was already against radical nationalism and the collaboration it led to during WWI. You might wonder why the Germans left him alone during WWII. Although he was barred from public life, he was never arrested."

"Biographies make life seem like a series of planned events, but I resist that. Life is far more random"

Why was that?

"It was due to his status. His early writings, some of which were even used as a basis for Flemish separatism, earned him great respect. In his famous 1896 essay, he was vehemently anti-Belgian as a young anarchist. He was also against colonialism and the military. However, he quickly renounced anti-parliamentarianism when he became a socialist. While Flemish radicals continued to praise his early works, he had already taken a different path, that of Belgian loyalty. In today's context, it's interesting that Vermeylen said Belgium couldn’t be divided because of Brussels."

What initially drew you to Vermeylen?

"He remains relevant today, particularly in his attempt to reconcile individualism with community. Vermeylen himself is also fascinating because of his unwavering honesty. That integrity is something we can still look up to in a moral sense. We’re all, to some extent, not honest enough. His steadfastness is an ideal; I even call the book a 'dream autobiography.' I started writing from the end of his life, as I wanted to do something different with the biography genre. Typically, biographies make life seem like a series of planned events, but I resist that. Life is far more random."

During his ban, he wrote a novel he'd long had in mind.

"Most agreed that Two Friends wasn’t as successful as his first novel, The Wandering Jew, but it’s still interesting. He used elements from his own life, transforming them into a message about serving the community without losing independence. His central idea was intellectual autonomy – a self-awareness that allows you to act for the greater good."

Something the VUB also strives for.

"Humanism was perhaps the most important pillar of his thinking. His ideals of humanity are more relevant than ever in today’s conflict-filled world. In that sense, the VUB indirectly owes him a debt."

How well is Vermeylen known at the VUB?

"Very poorly. He gave lectures for the student society Geen Taal, Geen Vrijheid before WWI. People tend to forget that he was associated with the ULB for a long time. Aloïs Gerlo, a former student of Vermeylen who later became the first rector of the VUB, wrote a glowing tribute to him after his death. Without the Flemishification of Ghent University, there would never have been a split between the VUB and ULB. It’s perhaps an exaggeration, but without Vermeylen, there would be no VUB! There’s your headline."

Silent Resistance: The War Years 1939-1945 of August Vermeylen is now available in bookstores. On 25th September at 8 p.m., the biography will be presented at the Letterenhuis, Minderbroedersstraat 22, Antwerp, where Hans Vandevoorde will discuss the book with Bruno de Wever. On 10th October at 2 p.m., Hans will talk with Koen Aerts of Cegesoma at Luchtvaartsquare 29, Brussels. You can register here.