Dreaming of a climate-friendly world and a sustainable society is encouraged. Hope is essential. But taking action is crucial. That’s the premise of The Land of Hope. In this book, launching on 18 June, VUB scientists and students collectively depict what the future could look like. We interview three of these students amid their exams and thesis deadlines. How sustainably are they living today? What future do they envision? Do they still dare to hope for a better world?

'The Land of Hope' will be launched on Tuesday 18th June at 15:00 with a public event.

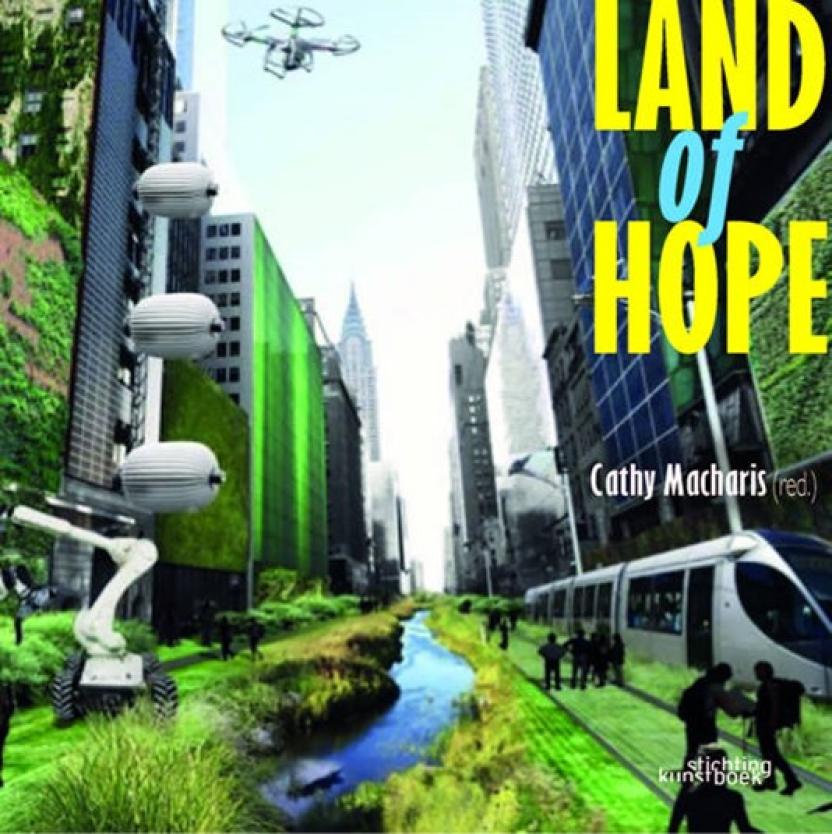

The realisation is now widespread: small changes alone aren’t enough. The climate crisis demands a profound transformation, upending the foundations of our beliefs. Everything must change. The scale of this challenge generates anxiety, despondency and a lack of perspective, says Professor Cathy Macharis, transition guru and coordinator of the House of Sustainable Transitions. “That’s the perspective we aim to provide with this book: visions of the future from the Land of Hope.”

A significant portion of The Land of Hope is engaging, accessible scientific work on themes like energy, buildings, mobility, economy, education, policy and food. One extensive chapter is based on the work of master’s students who took the elective Sustainability: an interdisciplinary approach. Their task: to envision a society that has successfully tackled climate change, biodiversity loss and overexploitation. PhD student and teaching assistant Ganiyat Temidayo Saliu synthesised the students’ ideas into a comprehensive future vision: the Land of Hope. We highlight a few themes with master’s students Lore Hermans (Applied Economics), Pieter Macharis (Civil Engineering), and Charlotte Vanhandenhove (Political Science). The first question is close to home: education.

In the Land of Hope, the university fosters not just knowledge but also systems thinking, co-creation and wisdom. Instead of one discipline, students follow interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary tracks based on their interests. Is this a good idea?

Charlotte: “The sustainability course we took together seems to be a step in that direction. As a political science student, I worked with future lawyers, economists, biologists, etc. You get different perspectives.”

Pieter: “Economics students wondered if a proposal made economic sense, law students if it was legally feasible. That was refreshing. The exercises I usually do revolve around cutting costs and maximising profits.”

Charlotte: “In the UK, you can already create a package combining, say, philosophy with economics or literature.”

Pieter: “Doesn’t that become too general? Such an approach can be enriching, but I wonder if there’s enough time to really delve and excel in your speciality.”

In the education of the Land of Hope, there’s significant focus on well-being. What do you think of that?

Charlotte: “It deserves more attention today. There is lots of pressure and lots of uncertainty. Many young people feel that way. For me, it’s mainly the question: did I make the right study choice? Am I doing what I want to do for the rest of my life?”

“I would find it hard to work for an employer whose values completely differed from mine”

And do you have any idea yet what you want to do?

Charlotte: “Not party politics, that’s for sure.”

Lore: “I worked at an insurance company for a semester, but I don’t see it as a career for myself. I used to think: I’ll get a 9-to-5 job, it doesn’t matter much, then I have my evenings and weekends free. Now I realise I also want to find fulfilment in my work. Consultancy? Several of my friends studying economics at KU Leuven have already signed contracts to start working at one of the big four after summer. I don’t see that suiting me.”

Pieter: “We also have lots of students aiming to earn good money at Deloitte and similar places. But some are thinking about a start-up or a career in government. I feel this is somewhat less prevalent in the Economics faculty at VUB. I’m currently considering applying to a European institution or a public body.”

That’s not badly paid either…

Pieter: “Money isn’t the decisive factor, but you do want to be able to support yourself.”

In the Land of Hope, graduates who need it receive financial support for a year. This gives them the space to find their ideal career path – one that aligns with their values and allows them to make a meaningful contribution to society.

Lore: “Values are important. I would find it hard to work for an employer whose values completely differed from mine, especially if the impact is directly visible: ‘If I work on this product, there are casualties in that country.’ No, I’d rather not.”

Company cars are a thing of the past in the future. Private car ownership is abolished, and we’ll rely entirely on public transport or shared cars. How do you travel today?

Pieter: “I share a car with my sisters, but they don’t have a licence yet. I only use it to come to Brussels when I need to for my job. Usually, I take the train.”

Charlotte: “I share a car with my brother, but he doesn’t drive. I use it every two weeks to commute to Brussels. By public transport, it takes me an hour and 40 minutes, by car it’s 40 minutes. I often take friends with me. But in Brussels itself, I don’t use it. I have a bus stop right outside my dorm. For €12.50 a year, you can get anywhere in 20 minutes.”

Lore: “I only use the car in emergencies – I’m afraid of driving in Brussels.”

“I love STIB and VUB. My two big loves!”

Can you imagine a life without a car?

Lore: “If there were shared cars nearby, yes.”

Charlotte: “And if public transport worked better.”

Pieter: “It’s a vicious cycle: people choose cars because they can’t get there by public transport, causing politicians to financially neglect public transport further, forcing people to rely even more on their cars.”

In the Land of Hope, a single company runs transport companies De Lijn, STIB, TEC and NMBS, forming a dense and well-connected network. One affordable subscription lets you travel throughout the country. What do you think of that?

Lore: “That would be amazing. STIB works very well – every five minutes there’s a bus, tram or metro.”

Charlotte: “I really love STIB! And VUB! My two big loves…”

Another visionary idea from the book: reopening all the city’s waterways. Could that work?

Charlotte: “I didn’t know this, but apparently 70% of the waterways in Brussels were covered over time, to make way for roads and industrial development – good for 15km. If you reopened and connected them, you’d have a new means of transport. Besides, water has a cooling effect when it’s hot.”

The private house, surrounded by a bit of grass and a wire fence, is relegated to the past. In the future, we’ll live in eco-conscious, cooperative housing with dozens of units and some common spaces. Could you live like that?

Charlotte: “Like living in a dorm, but for the rest of your life? (laughs) Sharing a garden or a laundry room doesn’t bother me, as long as you have enough private living space. For many apartment dwellers, this is already a reality. In Norway, local communities also do a lot together. In Belgium, we find that crazy because we’re not used to it.”

Lore: “I’d prefer not to be in an apartment, but those community vibes appeal to me. Working with a small community of neighbours or local residents in our own garden, eating locally… I would love that.”

Pieter: “I enjoyed my years in a dorm, but I can imagine needing privacy and peace after a long workday with the kids put to bed. Then I don’t need a neighbour reminding me it’s my turn to clean the communal kitchen. In terms of spatial planning, co-housing is interesting, as it requires much less space.”

“With the Ecotarian app, you can measure a food product’s impact on your health and the planet”

The residents of the Land of Hope eat seasonal and plant-based foods, occasionally with animal proteins. They order fish in advance via an app to prevent overfishing and food waste. Is that realistic?

Lore: “With my future garden, I could eat seasonally! Now, I don’t pay much attention to it. I rarely eat meat in the dorm. It’s expensive and I don’t miss it. Our generation is more frugal with meat products.”

Charlotte: “I have a seasonal calendar in the dorm, but I mainly use it when I’m out of ideas.”

Pieter: “Luckily, pasta pesto is always in season. Since January, I’ve drastically reduced my meat consumption, usually to once a week: when my mother buys a quality piece over the weekend. Honestly: not just because it has a smaller environmental impact, but also because it’s healthier. This topic interests me – I’m writing my thesis on eco-scores. At the same time as this book, Lise Vermeersch and some other VUB researchers are launching the Ecotarian app. It lets you measure a food product’s impact on your health and the planet.”

Are you strict about your diet?

Pieter: “If all my friends order a hamburger on a trip to Barcelona, I don’t make a fuss. I don’t keep the waiter waiting until I find the Spanish translation for ‘vegetarian burger’.”

A tricky topic for fashion-conscious students: fast fashion or sustainable brands?

Pieter: “This jumper is made from recycled materials. I prefer to buy clothes that last, not cheap T-shirts that tear after two washes. I always see it as a plus when brands focus on sustainability.”

Lore: “I’m also mindful of it, but I sometimes treat myself to something from H&M if I’ve worked a lot and have some savings. Thrifting is something I enjoy, but it can be exhausting. Sometimes it’s chaotic with all those racks to go through.”

Charlotte: “My interest in sustainability started with clothing. I enjoy shopping second-hand, but due to the hype, the nice pieces in places like Think Twice are often already gone. It’s also becoming quite expensive. The vintage clothes at Les Petits Riens in Brussels are still affordable, but then I feel guilty that I might be buying clothes other people need more.”

“Companies shift the responsibility to us. Why don’t they just act?”

Do you consciously avoid certain brands?

Charlotte: “I’ve never bought anything from Primark, and haven’t shopped at H&M for years. I try not to look at those brands to avoid temptation. I stick to websites with sustainable and ethical brands. For that, I use the app Good On You, which ranks brands on working conditions, material quality, animal rights, etc. I’m not perfect. I recently gave in and bought sunglasses from Meller.”

How hopeful are you, in general?

Pieter: “Many young people take initiatives and try to live sustainably, but they also see the government often lagging behind. That can be discouraging.”

Charlotte: “Companies say they’re willing to produce sustainably if there’s demand. They shift the responsibility to us. Why don’t they just start? I tried making my own zero-waste deodorant, but it took hours and I smelled worse than before. If you can launch a new flavoured drink every year, surely you can create products that improve society?”

Pieter: “Companies aim for profit, that’s true. Yet any product can be a success. That’s why I believe you shouldn’t just sit back but take the initiative yourself. This creates demand, and big companies can then supply it.”

Lore: “As an individual, you can only do so much. A more systemic approach is needed. That’s what we learned in the course.”

You can order the book here.