Abdulazez Dukhan (25) fled Syria with his family in 2014. Travelling via Turkey and Greece, he arrived in Belgium in 2017. He completed secondary school and went on to study Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). “Thanks to that camera, for the first time, I felt I could have an impact, and it gave me hope.”

You recently earned your master’s degree, a significant milestone that you described as bittersweet on social media. Can you explain why?

“Graduating was an intense experience. First and foremost, I was incredibly happy. I could hardly believe it, as it had been a long journey. The revolution in Syria began in 2011. For years, my family was on the run, first within Syria, then in Turkey and Greece. During that time, my family never allowed me to work. In Turkey, for example, one of my older brothers earned an income so I could finish secondary school. Financially, it wasn’t easy – living as a family on just one income. When we arrived in Belgium, my family urged me to focus on my studies. All those years, I didn’t have to work. As a result, I’m the only one in my family with a higher education degree. My two brothers and sister didn’t have the same opportunity—not because they weren’t capable, but because the circumstances didn’t allow it. They had to start working straight after school. So, I felt it was my duty to finish my studies. That played on my mind during the graduation ceremony. I had made it. At the same time, I was thinking about other Syrians. Many of them are living in difficult conditions today or are unable to continue their studies, often because they lack opportunities. I felt an obligation to show the world that it’s possible. Not to prove something to myself – I don’t need to do that – but to say, please give more chances to people who’ve spent years in refugee camps. And to those in the camps: trust in your abilities. You don’t lack skills, just opportunities.”

Abdulazez Dukhan took a portrait of a child who stayed in the refugee camp.

Your teenage years were tough. Did you feel ready for university when you arrived in Belgium at 19?

“At that point, I felt like I’d already lost too much time in my life. I wanted to start higher education immediately, but my secondary school diploma wasn’t recognised. I had to redo the last two years, which was a hard blow. Still, I tried to make good use of that time.

I quickly learned Dutch, and fortunately, I ended up at a fantastic school, Guldensporencollege Kaai in Kortrijk. Before starting my degree, I took a preparatory course, which helped—though I’d only had four hours of maths at a technical school level, so I had a lot of catching up to do. I felt that throughout the rest of my studies. What took my classmates two hours sometimes took me four. I had to work hard to get there. But my story shows that you can’t just write off young people who’ve lived in a refugee camp or fled from Syria. Just because someone’s had a difficult past doesn’t mean they can’t achieve something. Yes, it’s true: I sat through classes where I didn’t understand a thing. But also: in the first year, there were 150 of us, and when we graduated, there were only nine. And I was one of them.”

Did you face any prejudice at university?

“No. At VUB, everyone was treated equally. That’s what I love about VUB and its professors. But before I started my studies, people from different quarters told me it would be too difficult. I’m glad I didn’t listen to them. Just because I’d spent six years on the move didn’t mean I couldn’t study. I just hadn’t had the chance to do it. For me, there’s an important lesson in that: don’t judge people based on where they were born or what they’ve been through. You don’t choose those circumstances. Give them a chance, and then see what they’re capable of.”

Abdulazez Dukhan wants to continue telling his story as a refugee through photography.

Along the way, you discovered another talent. You started photography in a refugee camp in Greece.

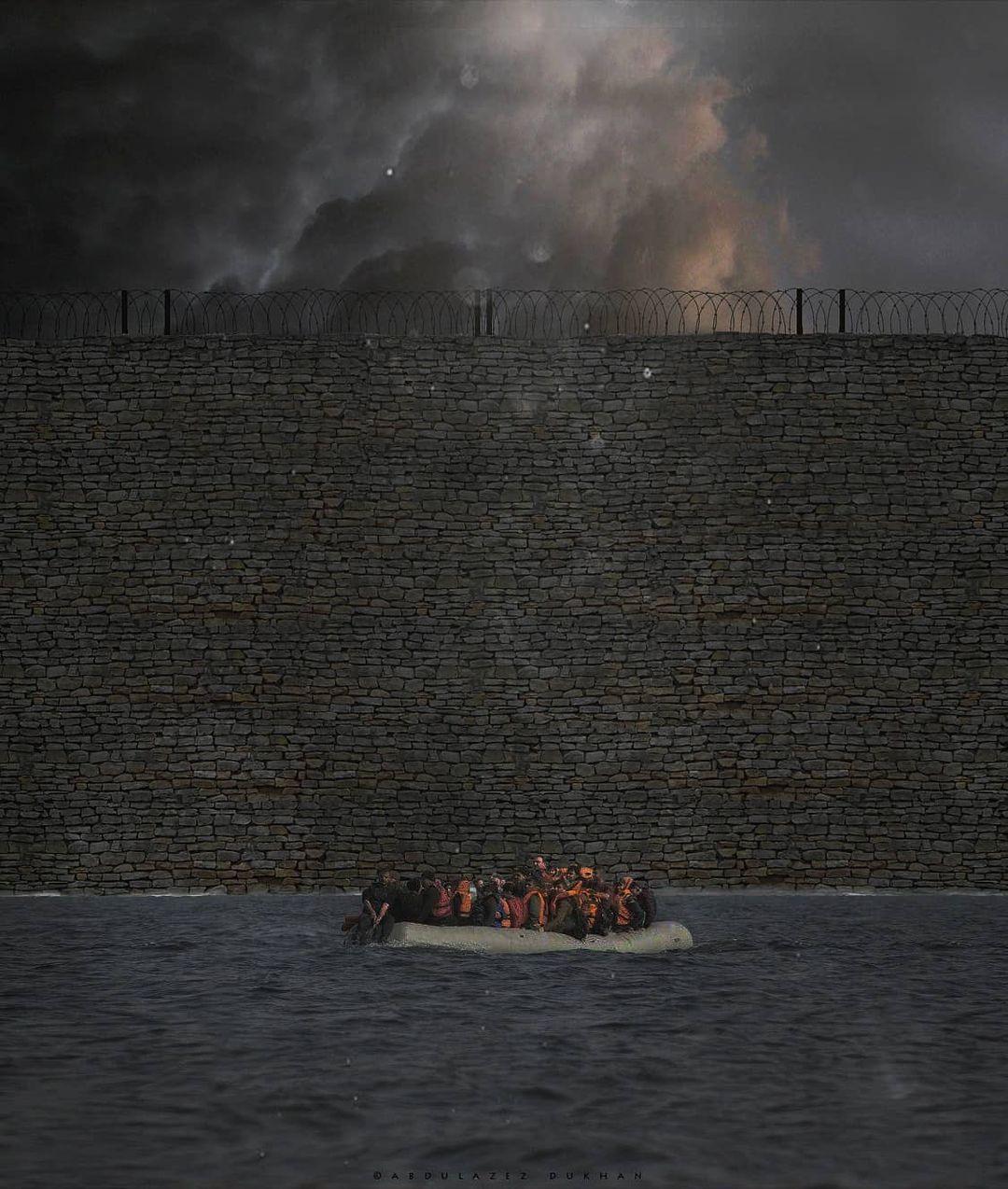

“And I’ve never stopped. Even though my studies were demanding, I always made time for photography. It’s my way of telling my story and, by extension, the stories of all refugees. I have to. Seven million Syrian refugees are scattered around the world. So often, we’re portrayed incorrectly. When you’re constantly misrepresented, you have to learn to tell your own story. Because if I don’t, others will do it for me. It can be exhausting, but there’s no alternative.”

Was VUB supportive of your commitment to photography?

“Yes, VUB has an international vibe. But I think VUB could speak out more about human rights, for example, by organising events that inform students about what’s happening in the world. With the student association Imara—of which I was president for a year—we tried to organise such activities. VUB could take this even further. It could also bring in more students from conflict areas and give them opportunities. There are so many talented people who simply don’t have the chance to study. That’s why, during my university years, I founded the Syrian Student Assembly, an association that supports Arab students who’ve only recently arrived in Belgium.”

What would you say to young people living in conflict areas who dream of earning a university degree like you did?

“That’s a tough question. I don’t want to sound like a wealthy person advising someone in poverty to save money. It’s not always that simple. But to everyone here who is doing well, I say: speak out. Don’t be greedy or selfish. History doesn’t remember cowards. Keep raising your voice against injustice.”

What are your hopes for the future?

“Before I graduated, I was already offered a job as a junior analyst. I want to focus on that now and work hard so I’ll have more freedom to tell stories again in the future. You know, one day, long ago, I was given a camera in a refugee camp. That’s how I started with photography and storytelling. Thanks to that camera, for the first time, I felt I could have an impact, and it gave me hope. If there’s one thing I wish for myself, it’s to find the younger versions of me along the way and give them hope.”*

*This is a machine translation. We apologise for any inaccuracies.