Few buildings in Brussels capture the imagination quite like the iconic Rectorate Building of the VUB, designed by modernist architect Renaat Braem (1910–2001). Completed in 1976, the Braem Building will officially reopen on 12 December, over 50 years later, following a comprehensive renovation. What were the early years of the 'Cigar,' 'M,' or 'Caprice des Dieux' like? What is its symbolic value in 2024, and what are the future prospects for this architectural gem?

In 1971, the commission for a new rectorate building was awarded to Antwerp architect Renaat Braem, who made it his mission to integrate the VUB's independent philosophy into his design. With its elliptical shape, unique murals, and concrete canopy, the Braem Building symbolises the VUB as an open and tolerant university, rooted in the principle of free inquiry. Three individuals involved reflect on the early years of the ‘Cigar.’

Rik Rottger, coordinator of CAVA, manages the archive documents of the Braem building.

"The Braem building was occupied several times in the past by students”

Was the Braem Building always this striking? Did the original plans look like this?

Rik Röttger: "It was one of the first buildings constructed on the VUB campus. From the outset, the architect wanted to create a prestigious project with a deeper message. He also sought to break away from conventional designs. That was no easy task in the 1970s, given the economic crisis. Significant discussions about the budget led Braem to propose a concrete, 'cheaper' structure. Initially, he envisioned three circles and a pond, but those plans were reduced to an oval-shaped building."

What do you recall from the design and construction phase?

"The building was completed in the mid-1970s, but what few people know is that Braem continued to create murals in the building well into the 1980s—some with his wife and others with a foreign muralist he invited over. In total, he painted 500 metres of murals on the six floors of the building."

As a progressive architect, did Braem manage to get everyone on board with his vision?

"Braem designed the building’s interior as one large open space without walls, which has been restored during the renovation. Back then, this was very modern—too modern, as the VUB soon added walls, turning the space into many small offices and narrow corridors. Today, those walls have been removed, restoring Braem's original vision."

What stands out most in the building's history?

"The times when students occupied the Rectorate Building in protest, often against tuition fee hikes. For example, in 1978/79, the ‘No to 10,000!’ campaign opposed increasing tuition fees from 5,000 to 10,000 BEF (Belgian francs). The archive contains wonderful photos of these events, including one of Yves Desmet (later editor-in-chief of De Morgen) actively participating as a student during one occupation."

The rector's office is on the fifth floor, as designated by the architect?

"Correct. Across from the office door, you’ll see Minerva’s owl depicted in the murals—a symbol of wisdom—reminding the rector daily of their duty to make thoughtful decisions. (laughs)"

Occupation of the entrance hall of the Braem building by students in protest against the increase in tuition fees in 1994 (photography by Egwin Gonthier, CAVA).

Charlotte Nys, VUB alumna and engineer-architect, contributed to the restoration of the Braem building

“Braem firmly believed that 'good' architecture could improve people's living conditions, thus making them happy”

What is the connection between the Rectorate Building and its architect, Renaat Braem?

Charlotte Nys: The Braem Building is a true embodiment of Braem’s worldview. He wanted everyone walking through it to learn how the world functions and, with that knowledge, be able to shape it. The building is a total work of art: its elliptical shape, murals, and canopy reflect Braem’s evolution from rational, functional modernism to an organic architecture inspired by natural forms. He called it a ‘temple of science,’ making it a perfect flagship for the VUB.

What is Braem’s significance in Belgian and international architecture?

"This building exemplifies Braem’s innovative yet controversial approach. Like many modernists, he championed functionality, but this building also inspires people to see architecture as a tool for social change. His belief that architecture can enhance social cohesion and improve living conditions is beautifully reflected here. While his work had a profound impact on Belgian architecture and its appreciation, Braem remains less known internationally because of his deep connection to the Belgian context. I see him as a key figure in modernism’s history, balancing bold, organic designs with social engagement."

Why is the Rectorate Building a treasure we should cherish?

"This building is a vital and unique part of Braem’s legacy, showcasing his vision of inclusive, community-focused architecture. For me, it’s an enduring example of how architecture can improve our quality of life or influence society's shapeability."

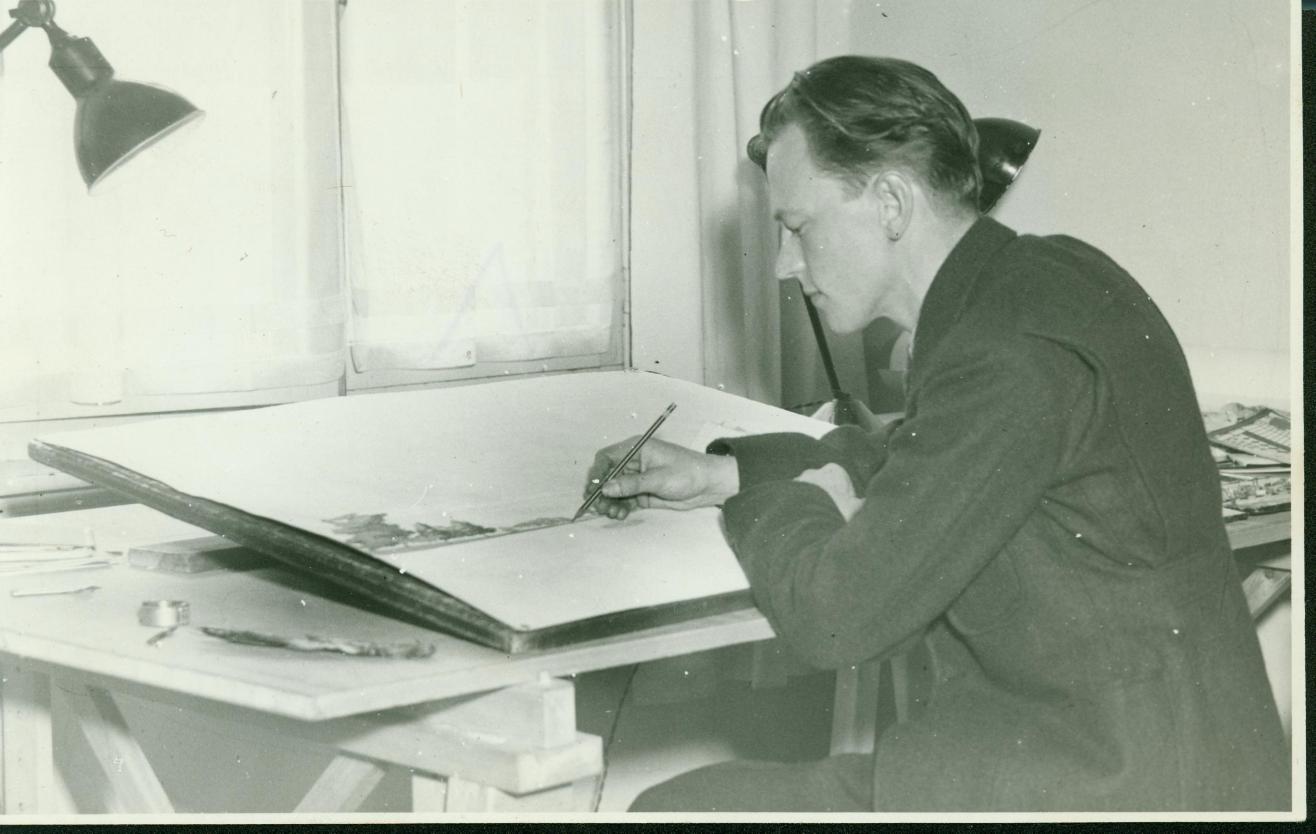

Architect Renaat Braem, together with his wife, also created the drawings for the Braem building, which was completed in 1976. (Photo: CAVA)

Tony Tillez, a VUB member from the very beginning, closely experienced the history of the Braem building's creation

"The higher your position, the more 'little windows' your office had in the rectorate building."

What is your first memory of the Rectorate Building?

Tony Tillez: "That memory dates back to the period before the building was constructed. You should know that Braem submitted several designs, including one featuring mushrooms, if I remember correctly. When the decision was finally made to go with the Braem Building as we know it today, it was originally intended to have open-plan spaces. Braem was certainly not a supporter of the ‘cubicle system.’ However, a former director, among others, felt that certain positions entitled one to a private office, and that set the ball rolling… resulting in the individual offices. A funny anecdote about that: the higher your position, the more 'windows' your office had. I also remember that Braem initially designed a reception area on the first floor. You can still see it in the beautifully laid-out floor tiles, which were later sacrificed for additional office space. Fortunately, during the restoration, these were reinstated to their original glory."

Are there any other facts about those early years?

"As long as I worked there, the lift only went up to the ground floor, not to the underground parking. Apparently, during the construction, it couldn’t be extended to level -1 because an emergency generator was installed in that area, and fire safety regulations made it impossible. This meant you had to park your car and then go outside to reach the reception via a ramp. Luckily, this was resolved during the renovations, and the lifts now do go to the parking level and are wide enough for wheelchair users.

Another fun fact from a different perspective: in the 1970s, there was a royal visit to the VUB. King Baudouin was due to visit the Rectorate Building—a unique event. In the hall, the rector and deans were ready to officially welcome him, and outside, many students had gathered. But what happened? One of those students, Cas Vander Taelen, loudly shouted, "Long live the republic!" as the king arrived—something that didn’t sit well with the VUB at the time. Remarkably, King Baudouin took the time to have a conversation with him. A second surprise that day."

Did you ever meet the architect?

"Absolutely. Both as a student and later professionally during inspections and the finalisation of, among other things, his murals. I remember him as an eccentric man, somewhat like his buildings. A bit introverted, an architect who was also an artist."

You spent many years working in the Rectorate Building. What was that like?

"That’s true. I started on the third floor, on the right, in what was then AIV. From there, I moved to the left side of the same floor, in the Finance Department. Then, from 1981 onwards, I led the PR Department on the ground floor. In the final years of my career, I had an office on the fifth floor, next to the rector’s. I didn’t really count the number of windows I had—three, four, five, perhaps? My favourite place, however, was the ground floor, because it offered the most freedom of movement and the chance to meet the most people, as the reception area was also located there."

Visit of King Baudouin and Queen Fabiola to the Braem building in 1977 (Photo: CAVA)

The Braem Building under construction (Photo: CAVA)

Renaat Braem (1910 - 2001)

- One of the key figures in post-war modernist architecture in Belgium.

- Worked as an intern in Le Corbusier's Parisian atelier.

- Deeply socially engaged, viewing architecture and urban planning as the ultimate tools to 'liberate' humanity.

- Not only a respected architect but also a writer, lecturer, painter, and more—his influence cannot be underestimated.

- Famously described Belgium as 'the ugliest country in the world,' criticising the nation's urban chaos.

- Notable works include: the social housing complex in Antwerp's Kiel district, the 'Modelwijk' in Laken, the Middelheim Pavilion and Police Tower in Antwerp, the Municipal Library of Schoten, and the Rectorate Building of the VUB.

Renaat Braem at the drawing board. (Photo: CAVA)