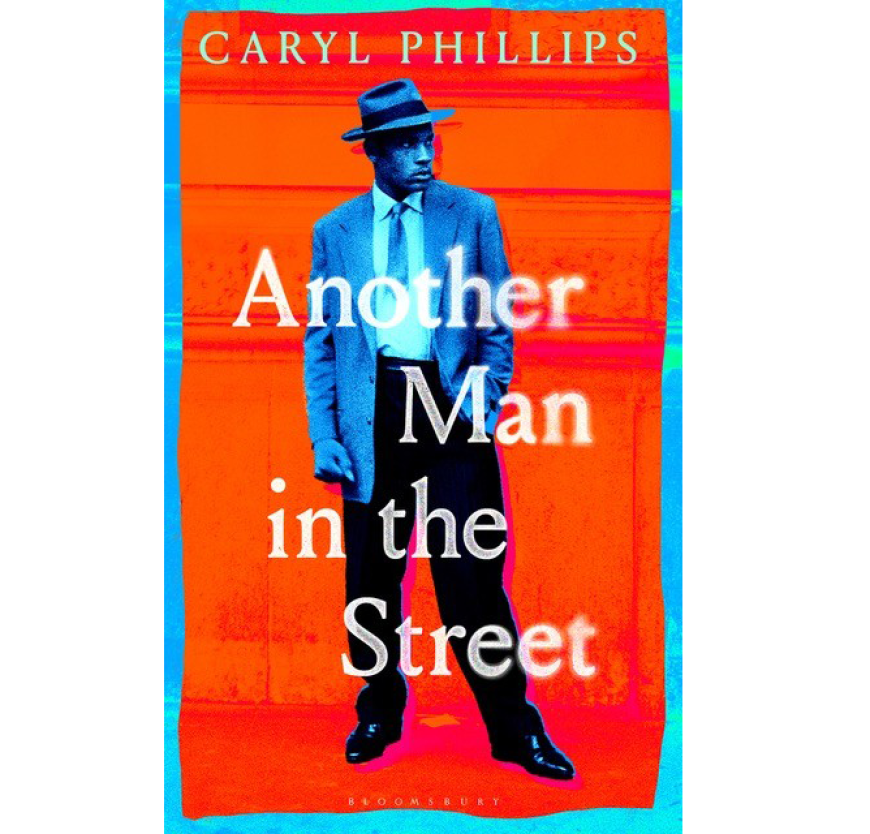

On May 6, renowned author Caryl Phillips will read from his latest novel, Another Man in the Street, at Passa Porta in Brussels. He will do so at the invitation of VUB literature professor Eva Ulrike Pirker. The book is a polyphonic exploration of migration in the UK. “It’s an attempt to spark empathy,” Phillips says.

Book your ticket now for the reading on 6 May 2025. Students get 50% off.

The direct inspiration for Another Man in the Street is the story of infamous London slum landlord Peter Rachman. His name became so synonymous with exploitation that “Rachmanism” entered the English language to describe the abuse of tenants. What drew you to him?

“When migrants arrive in a new country, the first thing they need is a place to live. Just after the Second World War, it was incredibly difficult for newcomers in London—particularly those from the West Indies and Africa—to find housing. Peter Rachman, however, did give them opportunities. Yet the establishment vilified him for the poor condition of his buildings. He came to be known as greedy and deeply unpleasant. But when I discovered he was a Holocaust survivor from Poland, I began to see him differently. Perhaps he had a genuine sense of empathy for outsiders because he had once been one himself.”

His fictionalised story is just one of many migrant narratives in Another Man in the Street. Victor, the main character, moves from the Caribbean to London. But there are also characters who migrate from the countryside to the city. What do all these stories share?

“They’re all about loss. When you migrate, you lose something. It might be your language, your family, your food or your music. What drives you to migrate, however, is what you hope to gain. The hope—and it is always a gamble—is that what you gain will outweigh what you lose, so the overall balance is positive. Many people migrate in search of a better future for their children. They’re willing to make personal sacrifices for that. That’s the common thread running through all the characters. For some, the balance is clearly positive. For others, not so much.”

“It’s precisely a writer’s job to offer a different perspective. That’s why so many writers around the world are imprisoned or exiled. We don’t conform”

Brick Lane street market in East London

You yourself came to the UK from the Caribbean as a baby. Later, you moved from Leeds to London. Today, you live in the US, teaching at Yale University. Do you recognise that drive?

“Absolutely. Every time you pack up and move, you hope for growth—whether it’s education, opportunity or finances. But just like in Another Man in the Street, real life doesn’t always let everyone realise their dreams. I’ve been living in the US for quite a while now, but things here aren’t exactly rosy at the moment. Sometimes I watch the news and think, ‘What on earth have I done?’ My children are growing up in Donald Trump’s America. That’s not the world I imagined for them. Was it really wise to settle here? That question still haunts me.”

Do you feel the impact of recent political changes in the US in your professional life—as a literature professor and a writer?

“Definitely. There have been major cuts to university funding, and some research departments have been shut down. I also sense a growing fear among international students—they’re more hesitant to speak out. There are stories going around about students, and even professors, having their visas revoked. I’m very aware that freedom of expression in my classroom is under pressure.

But as a writer, it doesn’t hold me back. It’s precisely a writer’s job to tell a different kind of story. That’s why so many writers around the world are imprisoned, or exiled. We don’t conform. And I won’t let my voice be silenced either.”

In Another Man in the Street, you don’t just tell one alternative story—you give us several. And you regularly switch narrative perspective. How did that choice come about?

“In the UK, where I grew up, people have a strong sense of history. To them, history follows a neat, linear path: first this king, then that queen, which led to such and such an event. But for me, as a young Black boy, there was no place in that timeline. That made me suspicious of dominant single narratives.

So if someone tells me ‘this is the history of Belgium’ or ‘this is the history of England’, I think: ‘No—it’s not that simple.’ There are so many different stories, and each one can be viewed from multiple perspectives. That’s why I enjoy switching viewpoints in my writing.”

You've lived in the US for years now, but you chose to set the novel in London. Why?

“The US is a nation built by migrants. It has a long literary tradition of migration stories. In British literature, migration features less prominently. Many Britons still hold onto the idea that migrants are a problem—or that they only play a supporting role. I wanted to set my book in a society where this kind of story is most urgently needed.”

"A novel is an attempt at encounter. And in that way, it’s an attempt to spark empathy"

How do you see multicultural society evolving in the UK?

“I see the same struggles as in the rest of Europe. Watch the Olympics or a football match, and you see diversity. But look higher up—in business or politics—and society suddenly looks very different. There’s a real tension between the reality in the streets and the structures of power. But I’m an optimist. I still have hope for the future.”

Do you see a role for yourself in that future—as a writer?

“Yes. I don’t want another generation of young people growing up without books where they see themselves reflected. That’s not the only reason I became a writer, but it was a key motivation. As a teenager—and even as a student—I was never given books that reflected the society I lived in.”

I don’t have a migration background, but Another Man in the Street gave me more empathy for the struggles newcomers face.

“Evoking empathy might actually be more important than offering recognition. A story that fails to spark empathy is just a history lesson. In literature, you have to be able to feel the fears and worries of the characters. That’s always my starting point as a writer.

Only afterwards do I think about the social injustices I want to highlight. The people—the characters—are the engine of what I do. I try to understand why they do what they do. And empathy isn’t just a tool to understand people—it’s a tool to change minds.

No one is going to shift their opinion about Syrian refugees based on a history lecture. But they might change their view after meeting someone from Syria—after imagining what that person’s life is like. A novel is an attempt to create that kind of encounter. And in doing so, it’s a way of inviting people to feel, instead of telling them what they should feel.”*

About Caryl Phillips

Described as “one of Britain's pre-eminent writers” (Guardian) and “one of the literary giants of our time” (New York Times), Phillips is the acclaimed author of 17 books of prose (among them novels, works of biography, travelogues and literary essays) as well as numerous works for the stage, the screen and radio drama. His works have won numerous prizes. Praised by critics for his versatility of style and approach to character, Phillips’s prose is also singularly readable and captivating, in keeping with the urgency of the subject matter his oeuvre treats and the crucial and timely questions it raises. Phillips has taught at universities across the globe and has been a Professor of English at Yale for more than twenty years.

Book your tickets now

Another Man in the Street > May 6, 2025 > at Passa Porta

This event is part of the Ties That Bind Us series, an initiative by three research groups from VUB's Faculty of Arts and Philosophy. It is also part of VUB's public programme, a programme for everyone who believes that scientific knowledge sharing, critical thinking and dialogue are an important first step to create impact in the world.

Do you want to dive into History, Literature, Philosophy or Arts Science?

Discover our study programmes:

*This is a machine translation. We apologise for any inaccuracies.