His scientific journey began in the village of his youth, and it will also end there. Hugo Thienpont was born in Gooik, graduated in 1984 as a civil engineer in applied physics at the VUB, completed his PhD six years later, and became a professor in 1994. He has just finished his final year as vice-rector for Innovation and Valorisation. “It was all at the VUB. I have known nothing else but the VUB.”

Professor in the making: Hugo Thienpont as a four-year-old boy standing in front of the blackboard

How did you become fascinated by science?

“As a young boy of about five, I was captivated by science fiction series like Star Trek, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and UFO. They had wireless phones, computers, lasers, rockets, robots... It all fascinated me immensely. I wanted to become an inventor. But, of course, you can’t get a degree in being an inventor. The closest was engineering.”

Do you come from a scientific background?

“No, quite the opposite. My father was a fruit grower, and my mother helped in the fruit business. But I was encouraged by my parents. My mother was interested in everything related to science and nature and she would take me to the library. I lacked nothing in that area. If I wanted a book, they would buy it for Hugo. I remember a very well-known volcanologist, Haroun Tazieff, giving a lecture at the Halle atheneum; my mother took me there to listen in the evening.

“My father only wanted one thing: for me to study. He wanted to become a pharmacist as a young man, but his parents wouldn’t allow it. So after secondary school, he had to leave school. That’s why he really wanted his son to continue studying. The field was up for debate. He didn’t want me to become an engineer; he thought one should have an independent profession – a doctor, a vet, a pharmacist, something like that, but certainly not an engineer. Until a friend, who was an architect, changed his mind.

“‘Our Hugo wants to be an engineer,’ my father told him. ‘How can you be so stupid as to want something like that?!’ ‘But Marcel,’ his friend responded, ‘that’s the hardest subject out there. If he can do that, he’ll easily find work and probably have a very nice career.’ And that settled it. I was allowed to study engineering. I was extremely relieved.”

“When I suggested that our research group should start collaborating with industry, our department chair protested, saying, ‘You’re prostituting our research group"

How did you end up in photonics?

“Just as I was about to start university, Professor Roger Van Geen, the future rector, launched a new field of study: applied physics. And that was exactly what I wanted. I was in the first cohort, and there were actually two major fields of study: nuclear physics and optics. That’s what I wanted to do: lasers and holograms. Science fiction becoming reality! Spectacular... but we were mostly taught by theoretical physicists.

“The only way to turn it into an applied science was to create something ourselves. Fortunately, Van Geen also established the Department of Applied Physics with the main goal of conducting research into light. He hired me as his first assistant. We started with empty offices, cupboards and laboratories. In the 1990s, we broadened the research field from optics to photonics. Optics studies the interaction of light and matter; photonics is the technology that uses these unique light properties to create new applications and, through this innovation, enhance quality of life.

“In the end, Prof Van Geen’s initiative was a success, albeit unexpectedly. At one point, Belgian industrialists announced in the magazine Technivisie that they expected the university to deliver widely trained engineers, not photonics specialists. With that, they argued against the master’s degree in photonics that we wanted to establish. When we continued to pursue the idea of training photonics engineers, I later received a request from them for a list of photonics students who had graduated with us. I reminded them that they had recently claimed they didn’t need them. Unfortunately, I said, all these top talents are now my PhD students with whom we are establishing a new research group: Brussels Photonics, or B-PHOT for short.”

“The VUB is much more of an innovation university than anything else”

Fast forward. What was your main intention when you took office as vice-rector in 2018?

“I had set three main tasks for myself. The first was to involve VUB researchers much more closely with societal needs. This included putting applied research for industry more in the spotlight.

“Believe me, I have nothing against fundamental research. You absolutely need that to make the leap to applied research, and applied research is necessary as a springboard to industrial research that has an impact on society. But until then, applied research was not highly regarded at all in our academic world, and that had to change urgently. Academy had to meet industry and society.

“My second goal was to steer research groups towards the large pots of money from the European Commission. Research funding at the VUB was very limited at the time and it still is. So, if you want to conduct top research, you have to get the money. When we started the vice-rectorate for Innovation and Valorisation, VUB research groups together brought in about €4 million a year from European projects. Today, that amount has increased to €20 million a year.

“Number three was better applied research infrastructure. The top innovation groups at the VUB could only continue to grow by investing in their own advanced research equipment and pilot lines. If you don’t have that, you can’t keep up in applied research and with industry at the European level, and certainly not globally. Then you are dependent on the goodwill of your external colleagues for access to their equipment, and that is finite.

“I think we've succeeded in all three aims.”

How important is innovation and valorisation for the VUB?

“It will surprise most people, but the VUB is much more an innovation university than anything else. Our most important research groups – about 20 or so – invest heavily in innovation but also highly value fundamental research. This combination ensures that you have the critical mass to continuously secure sufficient funding to be able to work for years without the Sword of Damocles hanging over your head. These are researchers who dare to undertake and invest and build a long-term vision.”

“Entrepreneurship might be more in your DNA than in your education”

So are you a scientist or an entrepreneur?

“Personally, I’m first and foremost an engineer, but an entrepreneurial one. That entrepreneurial spirit might be more in your DNA than in the education you receive. Essentially, you make a difference by thinking strategically and planning. You have to dare to take risks, invest, build and grow. With passionate employees, you can then create an impact. You need to take ownership and not expect the VUB to solve all your problems. Of course, the VUB will support your initiatives, but don’t wait for others to find funding, research infrastructure or staff for you. Take matters into your own hands.”

Is there a big difference between Hugo Thienpont the researcher and Hugo Thienpont the vice-rector?

“Yes, there is. I first worked for many years as a researcher in my own research group. It took several years before I realised that someone had to take the lead and devise a longer-term strategy if we wanted to grow and be of international significance. At that moment, you have to suppress the researcher in yourself and take on that leadership role, or you’ll just keep muddling along.

“And that, in my view, is the task of a vice-rector. An impactful vice-rector thinks about strategy. How can we grow? Where should we invest? And how can we roll out the strategy and successfully implement the future plan? A vice-rector shouldn’t really be involved in micro-management and daily tasks. That is the job of the Tech Transfer department, led by its director. So you have to suppress the researcher and professor in yourself to take on that leadership role.”

For some scientists, that hurts. How was it for you?

“It definitely hurts. If you have to leave the labs where you’ve fought for 10 years to equip them with the best equipment, where you know all the buttons and subtleties to conduct experiments: if you have to step away from that, it stings. On the other hand, that is compensated because you can work on the bigger picture. By stepping back as a ‘scientist in the lab’, I could take on more in my research by building a team of researchers, guiding them daily and thus creating more impact in the research domain.”

For some fields, such as humanities and philosophy, valorisation is not so obvious. How do you approach that?

“Five to 10 years ago, that was indeed the case. Today, it’s different. Humanities and social sciences can be valorised just as well. Take the Strategic Basic Research of the Flemish government; until recently, these were funds for natural sciences and technology, but now they also exist for socially oriented research projects.

“The European Commission also strongly promotes socially oriented innovation. Technology, after all, has a social impact, and that needs to be researched. Today, when you submit a funding application for a European project, there is often room for humanities and social science research groups to map out the impact of technology. So I would like to say to all research groups from the humanities and social sciences: please, don’t stay idle. Make sure you jump on the EU project bandwagon.”

“You need to take ownership and not expect the VUB to solve all your problems”

For many scientists, commercialisation is a dirty word. How do you convince them?

“Well, then they should follow their own credo and stop buying what is commercially available, right? Those are, after all, the fruits of researchers both from the university and industry who have marketed their knowledge: from mobile phones, computers, smartwatches, solar panels, medical sensors, to just about anything.

“It’s also important to know that we are a university and that, by decree from our government, we are not authorised to bring products to market or commercialise them. This also has to do with product liability.

“The real question is whether you lose your research independence by collaborating with companies. When I said back then that our research group should start collaborating with the business world, our department chair protested, saying, ‘You’re prostituting our research group.’ Those were her exact words. But that’s really not what we did, and it’s not what we do. In the first place, you only undertake research that you believe in and that is relevant to society and that aligns with your expertise and interests. Companies may come with bags of money, but if you don’t want to do that research or don’t have the expertise, you simply don’t do it.”

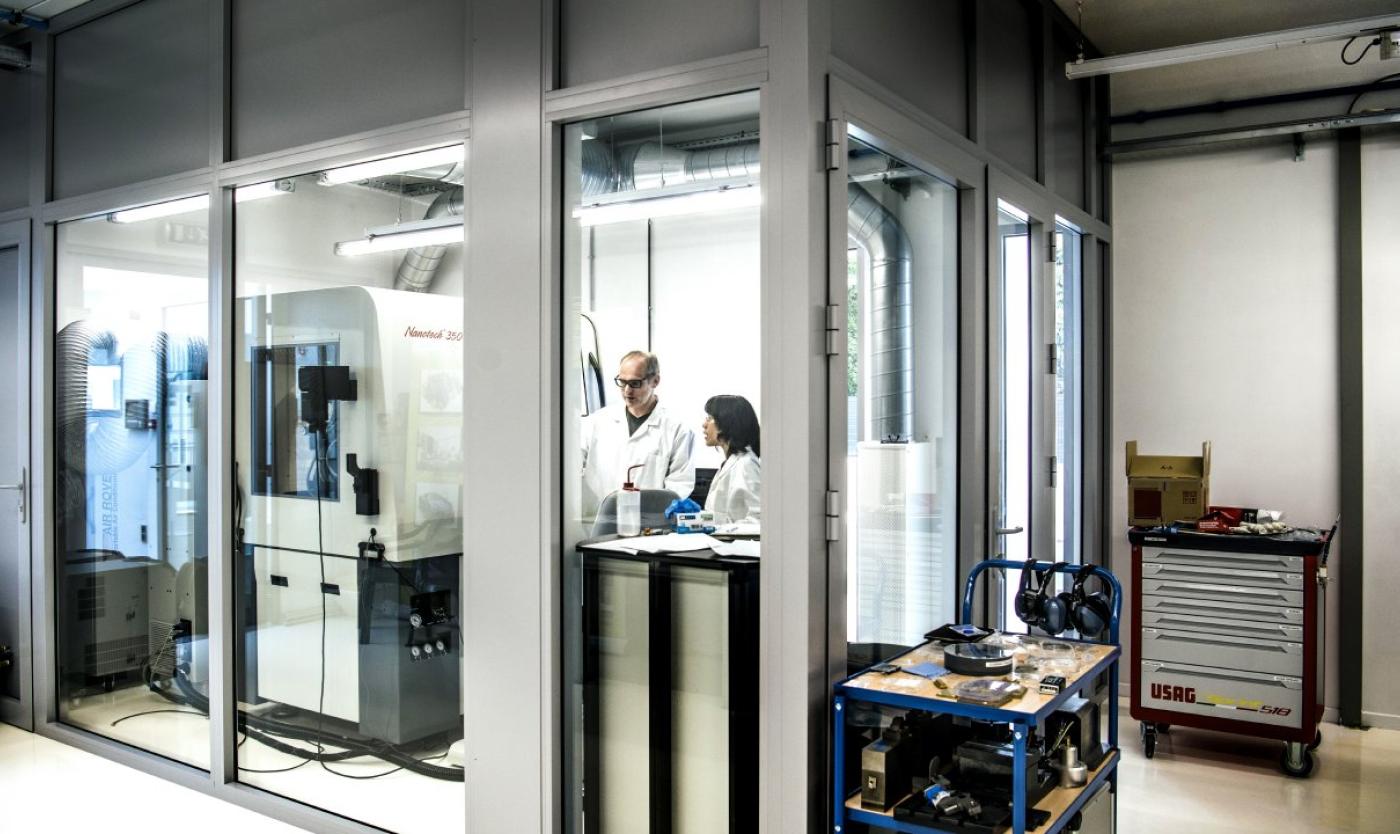

Your own research group, B-PHOT, has set up a laboratory in the village of Gooik where you grew up. Is this a source of pride for you?

“Well, first, I want to tell the story of how we ended up there. I had secured funding for heavy research equipment, but there was no place at the VUB to house it. So we had to find our own place. Brussels, with so much traffic and construction, was not ideal; we were looking for a location that was vibration-free. In photonics, we work with nanometre precision. Additionally, I felt that we could be more prominent in the Brussels periphery. And not on the Leuven side, where KU Leuven is, but on the west side, where the VUB is. Gooik was an inexpensive solution that pleased everyone.

“Until an anonymous email arrived at the rector’s office, suggesting that Thienpont was enriching himself personally in an ingenious way. Subsequently, the approach to our initiative was thoroughly reviewed, and it turned out to be perfectly in line with the legal requirements.

“That was 15 years ago. In the meantime, we have built a whole research campus in Gooik, which is regularly expanded.”

What does your future look like?

“My official retirement as a professor is in three years. But I would like to continue a bit after that. I now gladly hand over the vice-rectorate for Innovation to my colleague Prof Peter Schelkens, who – I am convinced – will continue this in a brilliant way. He is the perfect person in the right place.

“I am going back to my research group B-PHOT. Back from never really being away. I have always remained the director of the research group because I didn’t want to give up that position during my vice-rectorate. So, I’ve been working double duty. I hate goodbyes!”

Four successes for the vice-rectorate for Innovation & Valorisation

1. “We have been able to help many research groups grow by encouraging them to compete for European funding. We gave them an international profile by saying: VUB funding is too small, Flemish funding is too small, go to the European level. We have gone from €4 million to €20 million euros per year. Per researcher, the VUB is number one in Europe when it comes to securing funding from the European Commission.”

2. “The reform of the industrial research funds. We ensured that people could enter as starters, consolidators or advanced innovation groups, each with clearly defined and appropriate innovation funding. This way, groups can employ business developers and post-doc researchers according to their level of innovation to make the link to industry. That has been very important.”

3. “The VUB Foundation, an idea of former rector Paul De Knop. As a result of this, we have been able to attract donations, chairs and legacies. Examples are donations for cancer research or a legacy that establishes a chair. Chairs thus become important research instruments with a completely different funding source from the classic project funds from the government.”

4. “Finally, we have greatly strengthened our network outside the university by establishing the Fellows. This was an idea that came from professors Elvira Hazendonk and Joël Branson. Today, there are more than 200 leading professionals with whom we can collaborate and who give the VUB a face to the outside world under the motto Academia Meets Society. The people of Tech Transfer have worked on this and have achieved a tremendous success here. Each and every one of them is a leading professional, whom I will naturally miss very much.”