In 2025, the state pension age will rise from 65 to 66. By 2030, it will increase further to 67. The reasoning is well-known: with life expectancy on the rise, we need to work longer to keep pensions affordable. However, according to VUB professor Patrick Deboosere, this narrative doesn’t hold water. “The cost of pensions will increase in the coming decades, but it will remain perfectly manageable,” he explains.

Sign up for the pension debate in Bruges on 6 December!

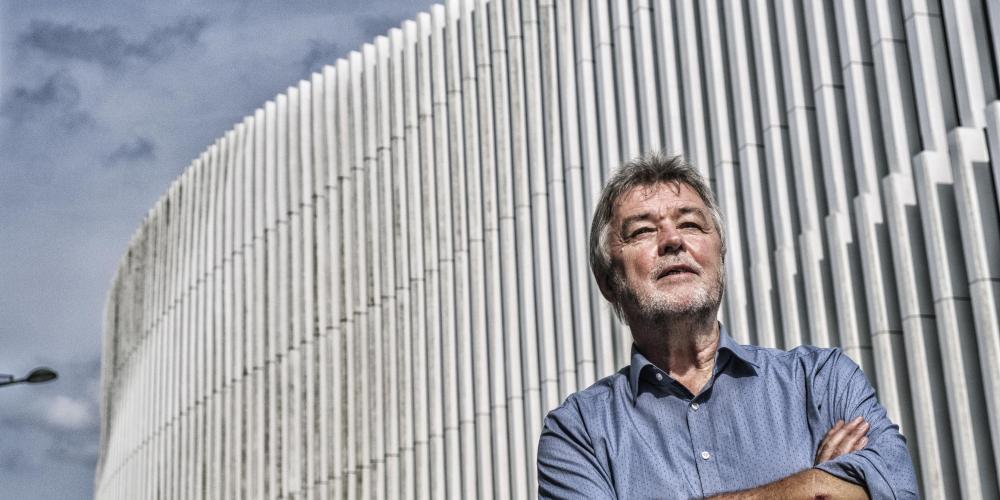

Patrick Deboosere, a demographer and professor emeritus at the VUB, formerly led the Interface Demography research centre, now known as BRISPO. On 6 December, under the banner of CTRL-SHIFT-DELETE, he will take part in a panel discussion in Bruges on the topic of affordable pensions. While he won’t be bringing sweet treats to the table, he does promise a metaphorical stick to tackle some stubborn myths—starting with the idea that rising life expectancy justifies pushing back the pension age.

“Life expectancy is increasing, which is a wonderful development. But it’s important to remember that life expectancy is an average. Humans as a species aren’t living longer; the key difference is that nearly all of us now reach old age.”

Didn’t our ancestors sometimes live to a ripe old age too?

“Absolutely. In 1850, for example, someone who reached the age of 65 could expect to live another 11 years on average. For those who made it to 85, there were about four more years to come.”

So what’s driven this increase in average life expectancy?

“It’s largely down to a dramatic reduction in child mortality and premature deaths. However, the biggest gains have already been made. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to add more years to our lifespan. In fact, in countries with high life expectancies, the rate of increase is noticeably slowing.”

How does that affect the pension debate?

“Well, for one, it shows that population ageing won’t continue indefinitely. By 2050, the pace of ageing will significantly slow. The pension debate shouldn’t focus solely on affordability but also on well-being. Biologically, we’re no different from our ancestors. The ageing process remains the same: our eyesight deteriorates, we move less smoothly, and our work efficiency declines.

Personally, I’m still working, but let’s be honest—a professor’s job is often more of a hobby. Or is it the other way around? (laughs) That’s a far cry from the realities faced by roofers, nurses, or airline pilots. Recent studies in the US estimate that around 40% of people in their 60s are in less-than-good health. This has to be taken into account. Raising the pension age effectively means taking away a part of people’s well-being. It’s paradoxical: first, we strive to help people age in a healthy and dignified way, and then, when they do, we tell them they have to work longer because there are now more of them.”

"The law is poorly designed. There’s no brake on the system"

But what if raising the pension age is necessary to keep pensions affordable? Surely more older people mean a greater pension burden?

“Currently, 2.6 million Belgians receive a pension, roughly 22% of the population. By 2050, the proportion of those over 65 will rise to 25%. So yes, the total amount we spend on pensions will need to increase if benefits are not cut. But that doesn’t mean they will become unaffordable.”

Can you put that into perspective with numbers?

“Today, we spend 11.2% of our GDP on pensions. Due to the wave of baby boomers now retiring, this will rise by nearly 2 percentage points in the coming decades, reaching 13% by 2050 before stabilising. That’s an annual increase of just 0.1 percentage points—exactly the same rate as over the past decade, during which pension spending rose from 10.2% to 11.2%. For comparison, the ‘tax shift’ under the Michel government—a reduction in employer contributions to social security—costs the state 2% of GDP every year. And that’s been ongoing for years now.”

How Much Do Other Countries Spend on Pensions?

“As mentioned, by 2050 Belgium will spend around 13% of its GDP on pensions. Five other European countries are already above that threshold. In Italy, the most aged country in Europe, pensions account for 16% of GDP. For a wealthy country like Belgium, reaching 13% is not an insurmountable challenge. By 2070, that figure is expected to rise slightly to 13.5%, but it should then stabilise as the number of new retirees balances out with those leaving the system.”

The Netherlands only spends 6% of its GDP on pensions.

“The Netherlands privatised its pension system quite early. That 6% represents the basic state pension paid by the government. Beyond that, Dutch citizens are required to secure private pensions through group insurance schemes. In Belgium, this is known as the second pension pillar.

The key difference is where contributions go. What we contribute to the state through social security payments, the Dutch pay into private pension funds. For the individual, the total contributions may seem similar, but the system introduces significant uncertainty, as those private funds invest contributions in the market. This also leads to greater inequality. Higher earners can contribute more and afford additional private insurance, while lower earners cannot, leaving them with far smaller pensions.”

You’re not a fan of Belgium’s second pension pillar either?

“I would regulate it better—or even phase it out as quickly as possible—because this system massively increases inequality. Not only do many people lack access to the second pillar, but it’s also distributed in a very unequal way. The lowest 10% of earners receive an average net increase of just €2 per month from group insurance when they retire. For median earners—those in the middle of the income scale—it’s €24 per month for employees and €145 per month for the self-employed. But for the highest earners, it can add up to as much as €16,000 per month.”

How is that possible?

“The law is poorly designed. There’s no cap on the system. High earners can shield a significant portion of their income from standard taxes by funnelling it into the second pillar, where it benefits from tax advantages. This allows them to build up a luxurious pension at the expense of other taxpayers.”

Have there been any recent positive changes to the pension system?

“The previous government raised the lowest pensions, making them better aligned with the cost of living. As a result, poverty has significantly declined over the last four years for the first time in decades. Surprisingly, this achievement was hardly mentioned in the run-up to the elections. There’s also been substantial progress for small business owners, although their contributions weren’t increased to match the improvements.”

You argue that raising the pension age isn’t necessary to keep pensions affordable. So why is that the dominant narrative?

“That narrative mainly serves to justify cuts to social security spending.”

The world needs you

This initiative is part of VUB's public programme, a programme for everyone who believes that scientific knowledge, critical thinking and dialogue are an important first step to create impact in the world.

As an Urban Engaged University, VUB aims to be a driver of change in the world. With our academic edcuational programmes and innovative research, we contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations and to making a difference locally and globally.