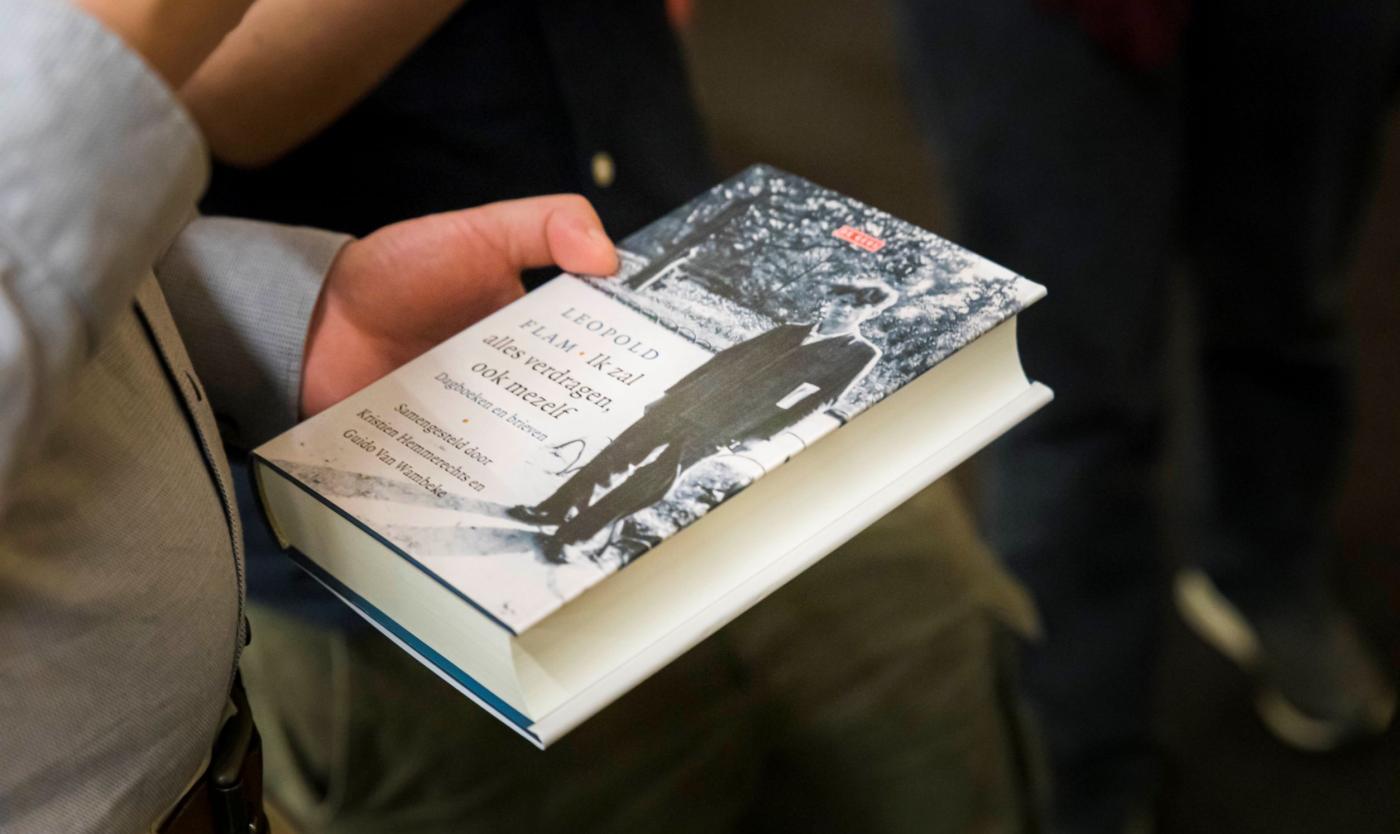

The recent CAVA and VUB debate around Leopold Flam was - as it should be - as confused as it was tumultuous and fascinating. The occasion was the publication of Ik zal alles verdragen, ook mezelf, a book composed by Kristien Hemmerechts and Guido Van Wambeke based on early diaries and correspondence of the legendary philosopher and ULB/VUB professor. What follows is an afterthought by moderator Max Borka, himself a former student of Flam, and former professor. Borka had the unfortunate task of leading a conversation between a vehement Hemmerechts and a pitying Willem Elias, also a former pupil of, and as professor emeritus of, the VUB, the driving force behind Leopold Flam (1912-1995) Een filosoof van gisteren voor een wereld van morgen, and the also recent Ecce Philosophus, two compilations of scientific contributions on Flam. It became a trench debate with lots of yeses and noes. About love versus a critical apparatus, or the fundamentally different way of dealing with such a legacy as an artist and scientist. About one's desire for a pageturner and bestseller, which the other said had led to a Flam for Dummies. About diligent hobbyists and lazy Flamists. And about Flam himself, of course, the well-nigh forgotten philosopher of failure who -nearly thirty years after his death- had suddenly revealed himself to be a successful writer, and then, according to others, a caricature of himself.

Max Borka

When, in the 1970s and 1980s, life on the newly opened new VUB campus was still largely dominated by the fratricidal struggle between the Maoist AMADA and the Trotskyist RAL, and we had alternatively founded the nihilistic three-man association ANada (A-Nada, Out of Nothingness, got it? ), there were two figures within the professors' corps who were considered hors catégorie in their monumentality: the invisible (and also largely forgotten today) Trotskyist and economist Ernest Mandel, then the most translated Belgian writer after Simenon, and Leopold Flam. Notwithstanding his blessed age, the latter argued, among other things, for a rebellious nihilism, as an alternative to other, hopeless forms of nihilism you could find a perfect illustration of on every street corner in the Brussels of those days, that of what he described very Sartrianically as the Walg's nihilism of that of 'a mere dissolute life'.

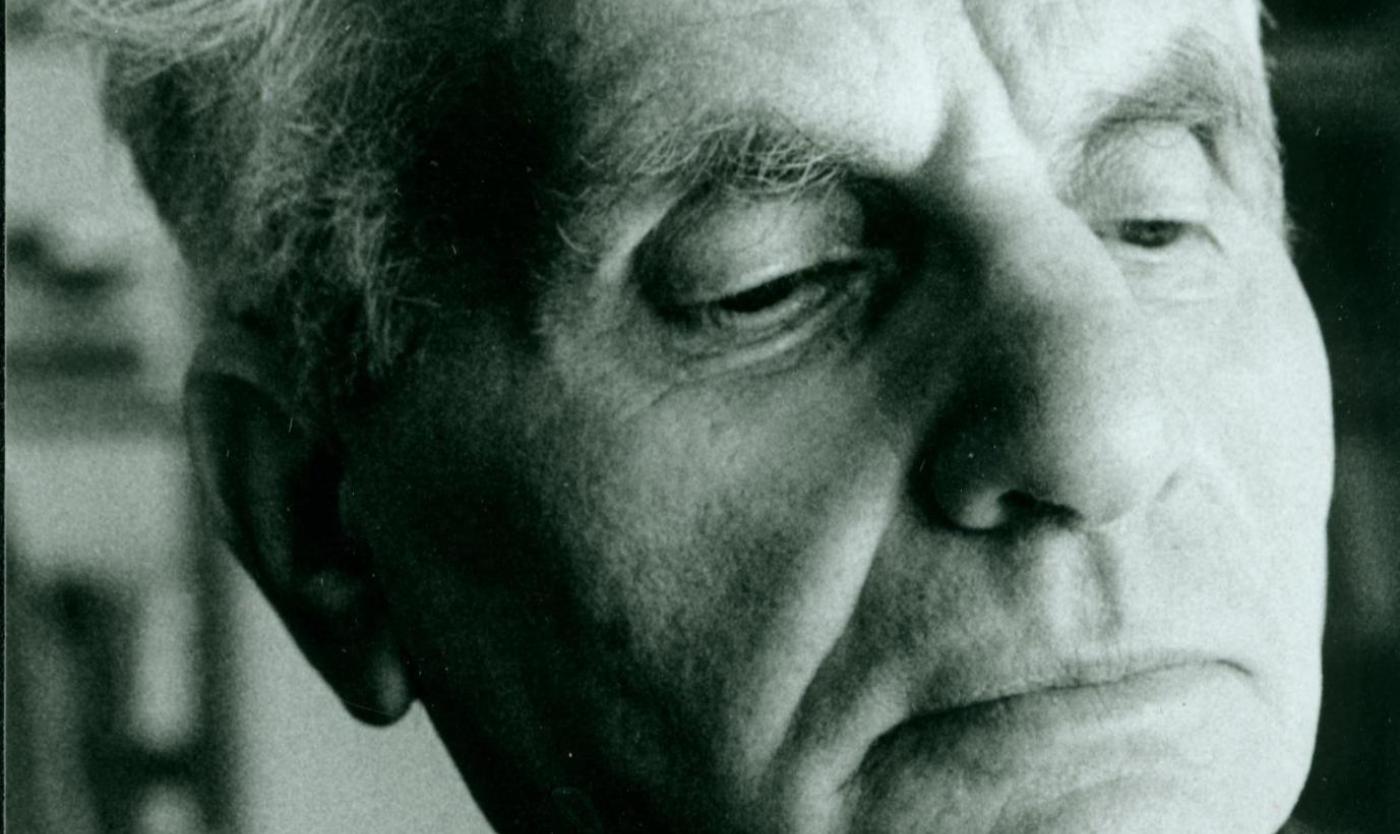

(c) Leopold Flam (c) CAVA / Jeanine Lambrecht

Today, people praise Flam as an icon, but in reality he was an outsider and loner, a loner, who preferred to keep it that way. His nihilism was not a closed system but an open, flexible, and dialectical method, offering every other loner the chance to survive and freely build a meaningful existence amidst "the horror of great Nothingness and a world totally decoloured since the death of God". "Rebellious man is under no illusions whatsoever," wrote Flam in 1966 in Self Alienation and Selfhood, " He counts on no recognition. He knows he is wholly finite, he needs neither comfort nor encouragement (...) He does not need the hope of a future paradise to oppose the gods with all his might (...), and if asked why he is rebellious, he can only answer: for nothing." For half a century, those words of this Rebel without a Cause were a credo during my many wanderings. But it was only when I recently read Ik zal alles verdragen, ook mezelf , in which Kristien Hemmerechts and Guido Van Wambeke reconstructed the first half of his life on the basis of his diaries, that I really realised that the horror Flam was talking about was never just a metaphor, and where this little man in a tailored suit and with the face of an eagle got the improbable strength, charisma and street credibility to draw me - and probably countless others - for life in this way. Here was a man who had raised himself from the underground in the most literal sense of the word.

The loner became mainstream.

After Flam's death, in 1995, things remained very quiet around him for a long time. Until recently, then, that book by Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke appeared. A pre-publication in De Standaard, interviews on VRT radio and in Knack, a review in Humo - the forgotten philosopher became a successful writer overnight. The loner became mainstream. However: was the Flam presented in the book really the real Flam? To what extent was the necessarily rigorous selection the compilers had made not simply a reflection of their own traumas and obsessions? To what extent had they remained blind to his undeniable tendency to automythologise? And before anything else: were these very individual soul-erratings allowed to simply be revealed to the public? In particular, former students who had appropriated his legacy for decades, Flamians or Flamists, screamed blue murder. Plenty of additional reasons for the VUB's Centre for Academic and Liberal Archives (CAVA) to organise a debate, although originally this had only to do with the fact that CAVA manages part of the Flam archive from which Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke had drawn.

Out of the blue

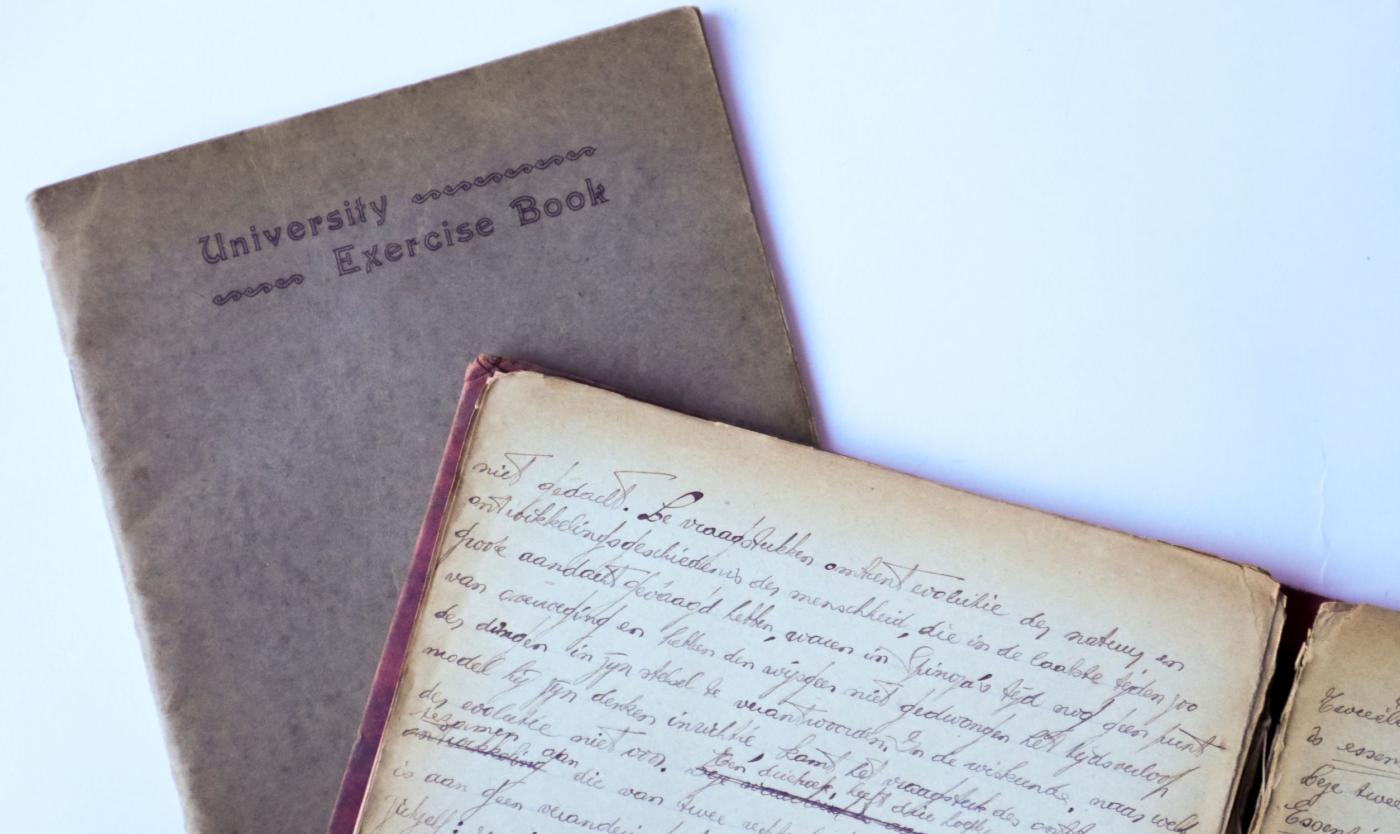

The debate was actually over when Hemmerechts proclaimed out of the blue - and publicly for the first time - that she had read virtually none of Flam's philosophical work. She said this proudly, defiantly, after yet another tease from Willem Elias. Perhaps it was to be taken with a mountain of salt. And yet. Only vaguely familiar with Flam, she had earlier stumbled upon his name by chance while researching for her previous book on Hubertina Aretz, who had been caught as a resistance fighter with Flam during World War II. "I was immediately carried away by that voice when I read his diaries. From admiration came love, and the realisation that she had in her hands a unique life story and time document: "How he grew up in Antwerp in a dark damp cellar, the child of penniless and illiterate Jewish migrants, and already as a child decided to read Spinoza and Kant. How he then survives the Holocaust as a communist, and eventually makes it to professor of philosophy. It remains miracle upon miracle. Sharing that was my only intention and approach."

(c) Fotoarchief CAVA

Kristienisation according to Elias

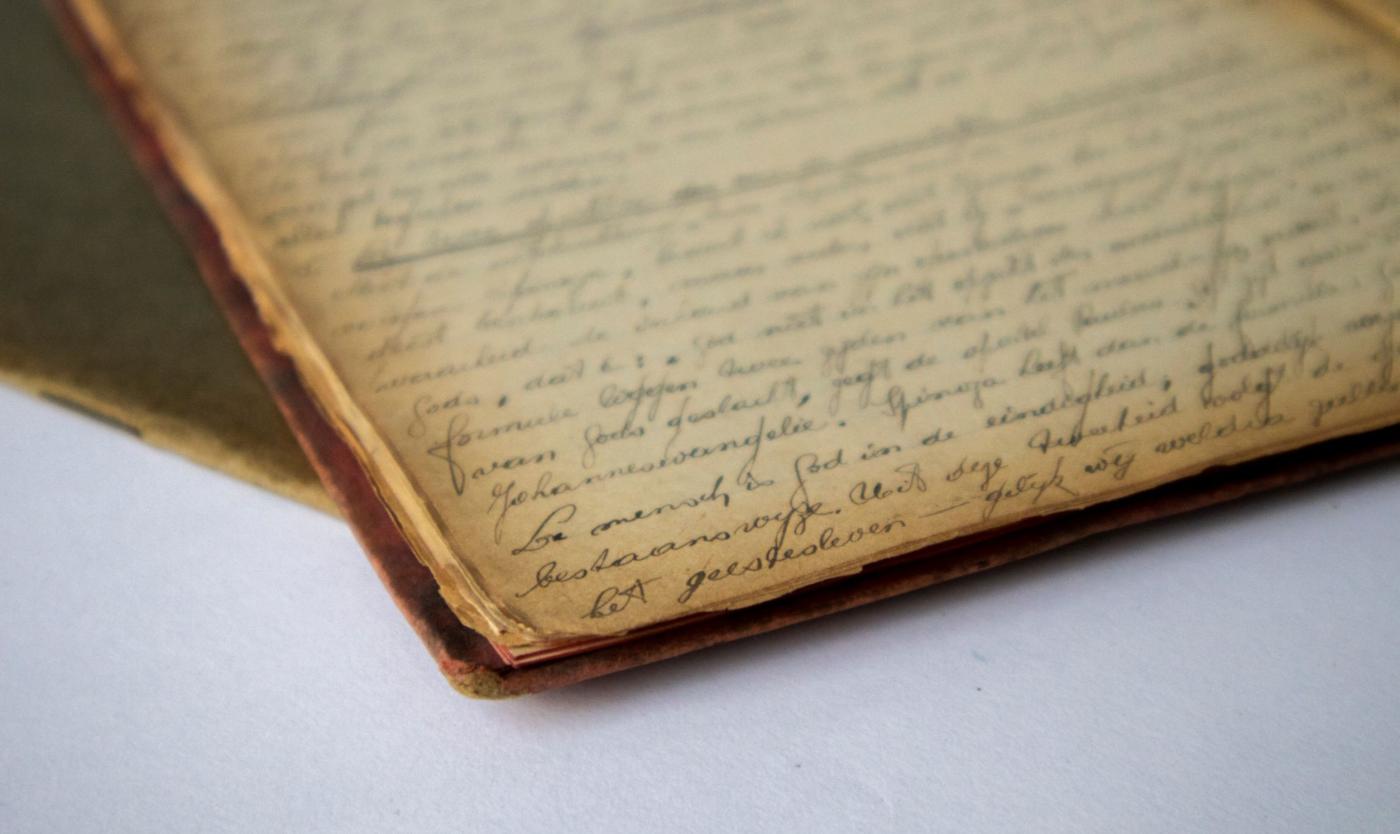

But is that possible, then? Just draw on those diaries of a philosopher, and ignore the rest of his oeuvre? And is that possible especially in the case of Flam, where those diaries are so intensely intertwined with his countless other writings, many of which are described as philosophical diaries because of their narrative thinking. In their selection, Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke deliberately limited themselves to the first half of his life, until 1957, when he became a professor, and began systematically using his diaries as a breeding ground for those more philosophical writings. The bulk of those writings also date from later. Still. For instance, in the absence of a critical apparatus worthy of the name, how can the careless reader of their diary know that the numerous entreaties of an already early atheist ánd communist Flam to God are not addressed to the Catholic God, but to the heretical Spinozist version of the unknowable Jewish Eternal, who, as a harmonious interplay of natural forces, can be scientifically fathomed? A Christianisation, Kristienisation according to Elias, was the result. As things were taken out of context or emphasised time and again without too much explanation, her book had also turned the proponent of Liberty and Enlightenment into a Christian Saint and hermit. A Flam for Dummies.

A maniacal writer

Not that Elias, or anyone else, wanted to challenge the literary merit of Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke's book. On the contrary. Often and especially inappropriately described as the Flemish Sartre, Flam had in common with the later Sartre that he was a maniacal poly-writer, preferring to start a new text rather than polish up an old one. This left his oeuvre with a not too good reputation in terms of readability. But with this book, that is completely different. While the rags to riches story is described by even the most ruthless critics as excellent fodder for a film screenplay, Flam as a writer is actually aligned with Dostoyevsky. And the debate then compared his raw self-irony to that of a Knut Hamsun in the cult book Hunger, and Louis Paul Boon, one of the rare Flemish writers with whom Flam had a relationship of mutual admiration.

A selection from two million words

In part, of course, this is due to Flam himself, and the typically Yiddish because laconic way in which he manages, for instance, to implode a pompous paragraph at the end with just a few words - a quality that, like the others, had been somewhat snowed under because of the multitude of writing. But it is equally to the credit of Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke that, out of two million words of diary mass, they made a selection of 140,000 words in such a way as to do full justice to those latent literary qualities. Moreover, they managed to weave fragments into a musical whole, which because of the many echoes and repetitions - another typical characteristic of Flam, which fully illustrates his obsessive character, and ma non troppo was reduced to enjoyable proportions - can best be compared to a conjuring fugue. That Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke manage to keep this up for more than 400 pages, with nothing but blanks, is in itself a tour de force.

While the rags to riches story is described by even the most ruthless critics as exquisite fodder for a film screenplay, Flam as a writer is even hoisted on a par with Dostoyevsky.

Plenty of reason to rejoice, one would think. Especially since, since Flam's death in 1995, his numerous books have been virtually unfindable, and Hemmerechts' book highlights aspects that are barely touched upon in the scarce literature on Flam. The importance of his Jewish origins, for instance, and the anti-Semitism he faced. His obsession with sexuality too, and his latent homosexuality, which he compensated for with tirades against homosexuality. Edoch. Even before Ik zal alles verdragen was in bookstores, Flamists of all kinds were up in arms, not only because of the way this Hemmerechts had 'appropriated their inheritance', but also because those intimate diaries were up for grabs at all.

(c) Fotoarchief CAVA

Loudest shouting Flamists left out

Hemmerechts had printed out a string of statements especially for the debate in which Flam loudly dreamed of publishing the diaries. She could have saved herself the trouble. After all, it was mainly the Flamists who shouted the loudest who failed to attend the dialogue he so cherished. What remained was Willem Elias, who, as a born recalcitrant, interpreted some of their laments, partly because he saw a point in them himself. For instance, in Sprokkelingen - gelukte mislukking in leven en werk van Leopold Flam, the book in a volume he wrote for Ecce Philosophus, he had also attempted to check the diaries against what had actually happened. His conclusion: the Flam as portrayed by Hemmerechts and Van Wambeke is a fiction, a perversion even, where it is not clear what is Wahrheit or Verdichtung. One example: the two brothers who Flam says died in his arms when he was barely six, according to Hemmerechts 'his great injury', more traumatic than his incarceration in Buchenwald. Even of the existence of those brothers, Elias had found no evidence to date. Not to mention that Flam had once added to his CV a stay in Auschwitz.

(c) Fotoarchief CAVA

Was the Flam presented in the book really the real Flam? To what extent was the necessarily rigorous selection the compilers had made not simply a reflection of their own traumas and obsessions? To what extent had they remained blind to his undeniable tendency to automythologise? And above all: were these very individual soul-erratings allowed to be simply revealed to the public?

Elias was joined by colleague Ann Van Sevenant, who had repeatedly pointed out in the past that Flam, through automythologising, "told a lot of things about himself that were not always true". She therefore felt passed over, excluded. Talked about a missed opportunity. To which Hemmerechts promptly replied that from the start she had contacted numerous Flamists, including Van Sevenant. No one had offered to help. Somewhat in desperation, Hemmerechts had found sixty volunteers through an appeal, who helped her decipher and transcribe the diaries. One of them, the most adept and driven, was Guido. Which in turn elicited growls from Elias about hobbyists. And: "I can only hope that something also happens to the words that were not selected".

Kristien Hemmerechts: "Fear was his basic feeling"

"What we selected is indeed representative of the two million words we were confronted with," Hemmerechts concluded, "On the other hand, however, we also wanted to appeal to readers who have no prior philosophical knowledge, but who are gripped by a strong life story. I myself have been a literary scholar for years, and I brought that knowledge into this project. Where necessary, we built into the text a brief commentary. But we did not want to inhibit readability. That is why the emphasis is also on the concrete: how, as a street urchin, he literally flees that cellar by working in a factory, even peddling hoovers, his money problems, his sex drive, his fights and crushes. Apart from everything else, I find that already very worthwhile, and I honestly cannot imagine that he would have made that up - there, then, in all solitude, and with no prospect of publication. Fear was his basic feeling, but we cut as soon as a long passage became too abstract, started to float. You may find that very shocking, but we live in times when books are competing with Netflix. As a writer, you also want to create a suspense arc where you take the reader all the way to the end. After all, that is the craft, the métier. You could make a diary where those longer passages are included, with countless footnotes. And of course, you would then create a different character. But also a very different book. Less readable, that much is certain."

CAVA and the archive of Flam

Leopold Flam's archive is kept in several locations. An overview can be found in Ivan Cloet's chapter 'A state of affairs in terms of archiving and inventorying the philosophical legacy of Leopold Flam. A trial to Flam archaeology' in: Leopold Flam (1912-1995) A philosopher of yesterday for a world of tomorrow (2010). This overview was resumed in 2021 and further supplemented by Willem Elias in Ecce Philosophus. Life and Work of Leopold Flam.

The Centre for Academic and Liberal Archives (CAVA) at the VUB preserves part of the archive. An overview and more info can be found on the website www.cavavub.be, in CAVA's online catalogue and in the ODIS database. It mainly concerns manuscripts, typescripts and diaries. Part of this archive was transferred to CAVA in 2022 from the AMVB . Material on Flam can also be found in some other archives kept at CAVA, for example the archive of the Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, archives of institutes founded by Flam such as the Centre for the Study of Enlightenment (and of Free Thought, or associations such as Aurora, and the Flemish Association for Philosophy, and also in personal archives such as those of Prof Hubert Dethier and Prof Jeanine Lambrechts. More info about CAVA here.

(c) Fotoarchief CAVA