For the first time ever, cryopreserved immature testicular tissue was reintroduced after 16 years in an infertile man who underwent chemotherapy in childhood. With this transplant, doctors and researchers hope to trigger sperm cell production and restore the patient’s fertility. The procedure was successful, and the patient is recovering well. In one year from now, the team will check for the presence of mature sperm. This transplant is the outcome of years of research of Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Brussels IVF, the centre for reproductive medicine of UZ Brussel. It is the consequence of another world first, because our hospital was the first worldwide to launch a cryopreservation programme for testicular tissue in 2002.

In boys who undergo radical treatments before starting puberty that can affect their fertility, testicular tissue can be preventively removed and frozen. This is done to preserve testicular stem cells, the precursors of sperm cells. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can destroy these cells, leading to infertility later in life.

Prepubescent boys do not yet produce sperm cells. The removed tissue contains stem cells that would normally produce sperm after starting puberty. The cryopreservation of tissue in young boys means we can potentially restore fertility later in life with a transplant.

Researchers of Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Brussels IVF, the centre for reproductive medicine of UZ Brussel, have now reintroduced several tissue fragments in a man who underwent treatment in childhood with chemotherapy which negatively affected his fertility. The procedure is part of a research project, funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) and the VUB (SRP-groeier), to assess whether such a transplant effectively restores fertility.

Evaluation of sperm production after 1 year

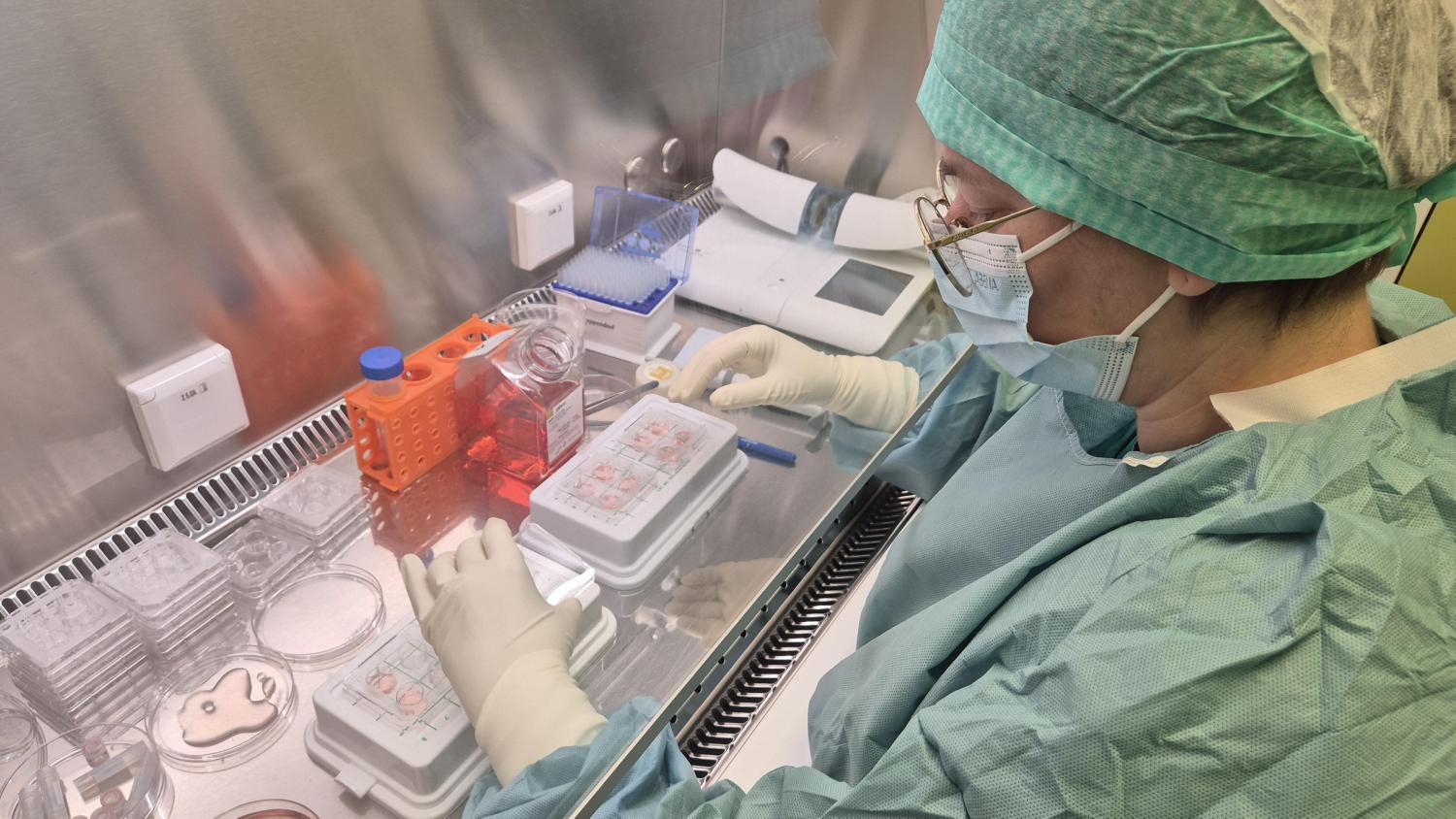

The transplant of testicular tissue consists of the reintroduction of four tissue fragments in the testicle and four in the scrotum. The technique is designed to make the patient’s body produce sperm cells autonomously. After the transplant, the patient will be monitored for one year, by means of blood work, hormone determinations, ultrasound examination and a semen sample every three months. The semen sample is examined for the presence of sperm. Because the tissue fragments are not directly connected to the sperm duct, the researchers do not expect sperm cells to naturally find their way into the semen sample. If the patient wishes to have children, ART will be necessary.

After one year, the transplanted tissue fragments will be removed and examined to check whether they produce sperm cells. Another small part of tissue in another part of the testis will be removed simultaneously to verify whether sperm cell production was also triggered there. This helps to understand how effective the transplant was.

Doctor Veerle Vloeberghs, staff member at Brussels IVF: “This is an important step in further scientific research to preserve the fertility of children with cancer or other blood diseases for the future. While the procedure is specifically designed to restore fertility, we cannot at this time guarantee that it will be successful or that patients can go on to have children. This treatment offers lots of perspectives for these young adults. They now have options that they did not have until recently.”

First step towards restoring fertility in young patients after exposure to chemotherapy or radiation therapy in childhood

Lifelong infertility is one of the most frequent side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. This is especially the case when high-dose therapy is used in children where puberty (and thus sperm cell production) has not yet started. Infertility is often considered one of the most far-reaching side effects of this type of treatment.

Professor Herman Tournaye, Head of Brussels IVF: “In 2002, UZ Brussel was the first hospital worldwide to initiate a clinical fertility preservation programme for young boys suffering from cancer or diseases of the blood, bone marrow or lymph nodes. Prior to their treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy, they and their parents consented to the cryopreservation of testicular tissue for subsequent transplantation. Some of these patients have now reached the age where they are considering having children.”

Professor Ellen Goossens, chair of the research group ‘Biology of the Testis’: “We have developed methods for cryopreservation and transplantation in animals which we have translated to humans. Since then, our hospital has frozen testicular tissue fragments of 141 boys. This tissue is preserved in liquid nitrogen at -196 °C. Currently we are working on a method for in-vitro production of fertile sperm. This would offer a valid alternative to transplantation in the event that cancer cells are detected in the tissue and to circumvent other forms of infertility.”