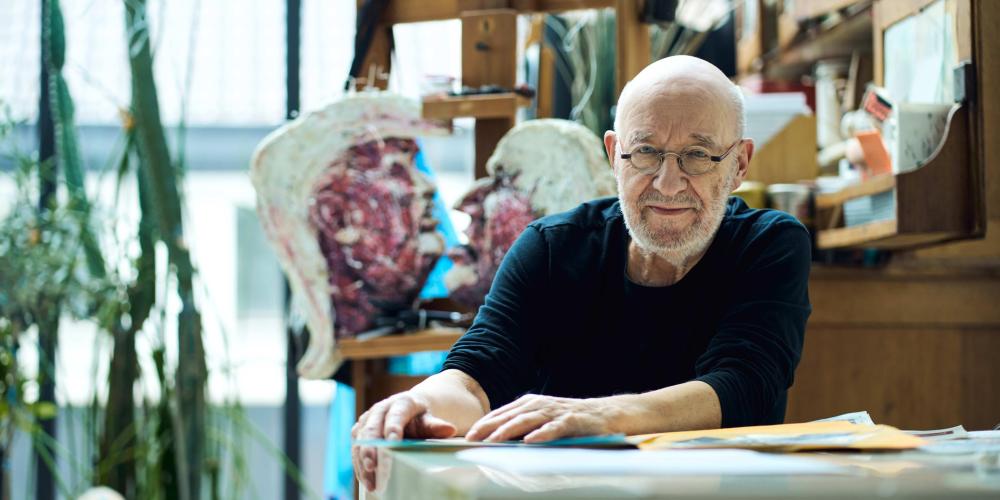

Gerard Alsteens (84) may no longer join in street protests – his bones are worn and his heart resists – but his sense of indignation remains undiminished. For 64 years, the artist known as Gal has channelled his outrage into razor-sharp political cartoons, including for Knack. In 2019, the VUB recognised his commitment to freedom of speech and press freedom with an honorary doctorate. Now, the university is showcasing a small but significant selection of his work in Mechelen, focusing on these very themes: several dozen of his older and more recent drawings, alongside designs created for six editions of Difference Day and a series of stamps.

The digital prints will be displayed for a month, but on the opening day, Saturday 24 August, the original works will also be exhibited. This is a rare treat for fans, who will even have the opportunity to chat with the artist, “health permitting”, as he cautiously adds. We had the privilege of visiting him. Gal lives and works near Schaarbeek station, on the stately Emile Zolalaan. Fittingly, the French writer was a notorious advocate of press freedom, best known for his open letter J’accuse.

Our photographer breaks the ice with a story: “I took life drawing classes with Gerard in art school. After a cycling accident, I couldn’t use my right arm. I wanted to quit the class but he wouldn’t let me. He made me draw with my left hand. It was a revelation. I often continued drawing with my left hand afterwards, as I found I could work more freely that way.”

Gerard is pleased to hear this. “Blind sketching – where you look at the subject and not the paper – has a similar effect. You may not capture the details, but it frees you, and the result is often very expressive. Even now, I enjoy opening myself up to adventure while drawing. I still work in a very traditional way, with pastels, ink, watercolours... Many of my visual ideas emerge from forms that develop by chance as I draw or paint.”

Your work requires careful observation, with layers of meaning to uncover. The recent memes about Donald Trump’s injured ear drew many comparisons to Vincent van Gogh, but in your drawing for Knack you gave him a conductor’s baton and a halo. What was your thinking?

“I didn’t think the Van Gogh comparison was relevant. I want to be a political analyst, which is something I also value in other cartoonists – their work has political significance. That attack was horrific, and luckily Trump survived; otherwise, he would have become a martyr. At that time – before Kamala Harris became the Democratic candidate – he was conducting not only the Republican but also the Democratic Party. I initially wanted to add a few drops of blood to the baton, but in the end, I felt that was a step too far.”

You drew Trump surrounded by his bodyguards, echoing the image of the crucified Jesus in a Rubens painting. Why is that?

“I’m glad you noticed that. Baroque painters often used triangles in their compositions. It also evokes the famous photograph of American soldiers raising the flag in Japan during World War II.”

You often say that outrage fuels your work. Where does that outrage come from?

“I’m a child of the war, born in 1940. My parents were grape growers in Overijse, where V1 bombs frequently flew overhead. My mother and sister would hide in the cellar, while my father, twin brother and I stayed in the kitchen. As if men were somehow bombproof! I vividly remember the fear in my father’s eyes and the whistling sound of those flying bombs. I associated that chaotic noise with the decorative curls on the ornamental tiles in the kitchen. Those moments deeply affected me. Perhaps that’s where it all began?”

"I recently pieced together a sculpture of a 'skull tower' with Prime Minister Netanyahu's head at the top."

What about your interest in politics?

“My grandmother worked as a maid for wealthy families and started reading La Libre Belgique. I can still picture the photograph of Stalin, dead on his bed. My grandparents explained that he had been a dictator and what that meant. At boarding school, I was introduced to Van Gogh and Goya. The horrific, journalistic war images in Goya’s Desastres de la Guerra left a lasting impression. Since then, I’ve been fascinated by power and its abuse. Nothing is more dangerous than politicians who misuse their power.”

You were in your 20s during the 1960s, a decade when authority was widely questioned. What impact did that have?

“I once ‘suggested’ to my students that they join me in occupying the Museum of Fine Arts in the late 1960s, but they weren’t too keen! The protest movement was more centred on Leuven back then.”

What do you think of the activism of today’s young people on issues such as the climate and Gaza?

“I fully support them. Maybe young people today are a bit calmer than those of May 68? What I do miss are the debates. Journalists used to be invited to universities for debates with students. I have the impression that it’s mostly right-wing student groups that still engage in this. But maybe I’m missing things? The way we communicate has changed completely.”

You’ve taught throughout your career, at Sint-Lucas and Rhok.

“And I’ve always enjoyed it. That job provided security, and I had time to work for publications like De Nieuwe and De Zwijger on the side. That was my ‘soapbox’: it didn’t pay fantastically, but I had complete freedom. Marc Grammens, the editor of De Nieuwe, often asked me what my cover drawing would be about, then he had a theme for his main article. I’ve always enjoyed an incredible amount of freedom.”

Has any of your work ever been rejected?

“It happens. Or I might adjust it slightly. I recently put together a sculpture of a ‘skull tower’ with Netanyahu’s head on top. For my weekly contribution to Knack, where I’ve worked since 1983, I took a photo of it and added the caption ‘Übermensch’. The editor-in-chief, Bert Bultinck, thought that was a bit too much. He felt it worked just as well without the word. We discussed it briefly, and in the end, it was published without the word.”

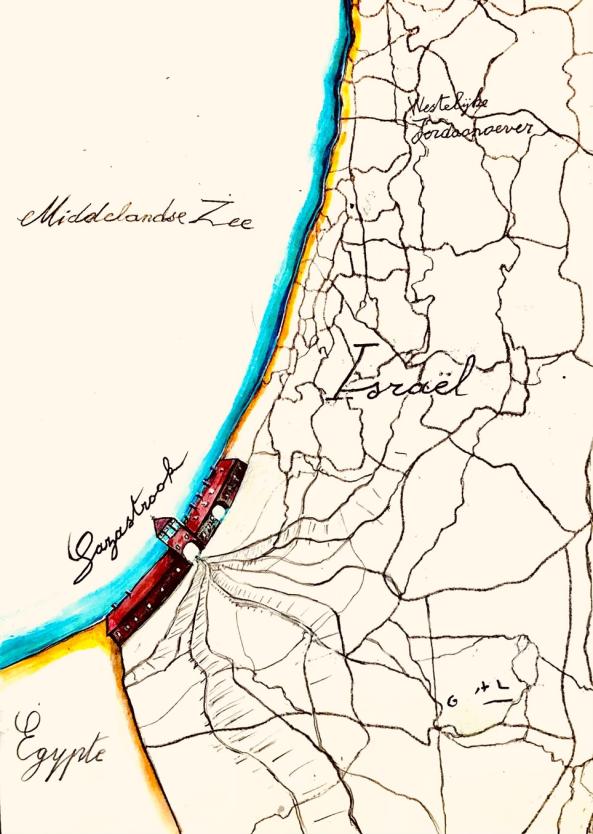

So Gaza remains a minefield?

“I recently tilted the iconic building of Auschwitz and placed it in Israel. It’s crude, I’m aware. I hesitated for a long time before finally making the drawing. It was published and received a huge response.”

Does this conflict still anger you?

“After the war, we rightly felt compassion for the Jews, but a poor agreement came out of it. Since then, the Palestinians have been constantly displaced. I’ve been drawing for 64 years, and it’s been going on that long. Every Israeli prime minister has followed the same approach, empowered by US support.”

And what about Hamas’s actions on 7 October?

“It was horrific, and I’ve drawn about that as well. But that doesn’t mean Hamas is responsible for those 40,000 Palestinian deaths, as Bart De Wever claims. This terrible situation has grown over the years and then burst open like a boil. Hats off to Caroline Gennez, who condemned Hamas’s actions but also placed them in a historical context.”

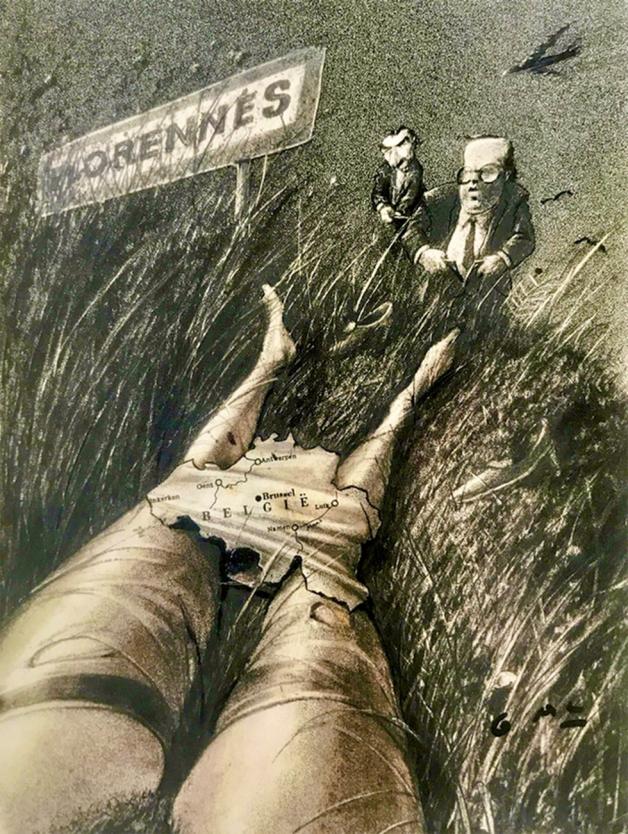

Is the pressure on political cartoonists greater or less than it used to be?

“As I said, I’ve had an incredible amount of freedom, and only experienced censorship very occasionally. During the missile crisis, with the massive protests against the deployment of cruise missiles, Sus Verleyen from Knack refused to publish one of my drawings. I had depicted Belgium as two bare women’s legs in a ditch with knickers around the ankles, while Wilfried Martens and Leo Tindemans zipped up their trousers in the background.”

And what did they think of that?

“I once asked Martens. He was fine with it. ‘You have your job, and I have mine,’ was his response. Tindemans was less comfortable with it. I once gave Bart De Wever a Hitler moustache in the shape of the Vlaams Belang logo. He himself said that this is the freedom we have in our country.”

Do you still find blind spots in your thinking? You’ve always admired Picasso, for example. He’s now under fire as the archetype of the misogynistic macho artist who used and discarded women.

“As a student, I was deeply impressed by Picasso. He was an unreachable talent who mastered an incredible range of techniques. But he was also a small, vile man – 1.62m tall – and a coward, fleeing from one woman to the next, covering his tracks. Not a pretty picture. The only positive spin you can put on it is that Picasso’s famous periods – blue, pink, cubist, surrealist – wouldn’t have happened without those relationships. Each period is linked to the influence of one of them. For example, it was Dora Maar, a very intelligent and talented artist, who convinced him to make Guernica an explicitly political work.”

Older white male artists sometimes complain that they’re out of favour and struggling to get by. What’s your view on that?

“Many great female artists were never taken seriously or vanished into the folds of history. Marcel Duchamp’s famous urinal was actually an idea by the Dada artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. The pendulum is swinging the other way now. That’s how it is, and you have to accept it.”

The VUB is deeply connected to Brussels, and so are you, it seems. How do you feel about the city?

“I once built a house in the countryside, but I never lived there. Brussels is the only real city in Belgium and a mirror of today’s reality. I especially love this city because it’s where I liberated myself, in every way. We cultivated grapes at home, but we had no culture. I worked through that inferiority complex in Brussels’ museums, cinemas, libraries, theatres and vibrant life. All of it perfectly accessible by tram. I soaked it all up like a sponge, eagerly and greedily, and shared it with pleasure. I wish every young person a student life like that.”

Gerard Alsteens designed stamps on press freedom. They are also exhibited by the VUB in Mechelen during Maanrock.

VUB x Gal: Free to Question Everything

In anticipation of the upcoming edition of the Maanrock festival, Gerard Alsteens, better known as Gal, has collaborated with the VUB to curate a selection of 20 powerful drawings from his extensive body of work, exploring freedom of expression and the threats to if. You are invited to view these works at the VUB Pop-Up Café at VC De Schakel in Mechelen on 24 and 25 August. On 24 August at 16.00, there will be a meet-and-greet with the artist himself. The exhibition will remain open until 28 September.

Gal in the VUB Archive

“…about speaking truth to power”: that’s how former VUB rector Caroline Pauwels described the work of Gerard Alsteens. She facilitated the donation of his drawings to the Centre for Academic and Secular Archives (CAVA), the VUB’s university archive. CAVA digitised the work and, in 2023-2024, added descriptions to make the more than 4,000 drawings searchable.