VUB research shows many people came from the Low Countries and were politically active

The question as to what extent newcomers from abroad should have a political say in their new place of residence is one that occupies many minds. This was also the case centuries ago. In a paper published in the History Workshop Journal, Bart Lambert, medieval historian at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, investigated the political participation of immigrants to England during the 15th century. His conclusion: “The non-English nationality of these immigrants was not in itself an obstacle to their participation in political life. Much more important was their economic status.”

Although Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries was plagued by conflicts such as the Hundred Years War and pandemics such as the Black Death, for England this period was by no means one of splendid isolation. “Our earlier research had shown that England, then still a separate kingdom, attracted many migrants from continental Europe in these years,” says Lambert. Based on the lists of a tax levied specifically on residents of non-English origin, he and his colleagues found that at least 1.5% of the English population during the 15th century had been born abroad. “That may not seem much, but it is comparable to the proportion of first-generation migrants in the population of England at the beginning of the 20th century,” says Lambert.

Many cities also had higher concentrations of immigrants: in London at least 7% of the population was born abroad, in Southampton and Bristol more than 12%. These newcomers came from all regions of Western Europe, including present-day Belgium and the Netherlands. In the south and east of the country, specialised craftsmen from the Flemish, Brabant and Dutch cities, accompanied by their wives and children, were the most numerous group among the migrant population. Most of these people were engaged in the fashion and luxury industries, as shoemakers, tailors, goldsmiths and producers of accessories, or in beer production.

Fleming was mayor of Lincoln

Lambert then examined the extent to which these immigrants could participate in the political life of their new English home. “At the national level their influence was limited,” he says, “but at the local, urban level they were remarkably active.” He searched through numerous urban source series, both from small towns and large provincial centres, and found countless examples of immigrants making their voices heard in local public assemblies, denouncing malpractices before the town council or sitting as jurors in municipal courts. In many places, immigrants stood for and were elected to civic offices. For example, Southampton and York, two of the largest cities in the country, were governed by an Italian and a German mayor. Here, too, people from the Low Countries made their contribution. John Wetter, for instance, an innkeeper from Flanders, became mayor of Lincoln, a medium-sized town in the east of England. Lambert noted that the fact these people came from abroad had virtually no impact on their political careers. Their economic position did: it was mainly the richer immigrants working as merchants or craftsmen who won top positions. Female immigrants remained excluded from local politics, but so were English women.

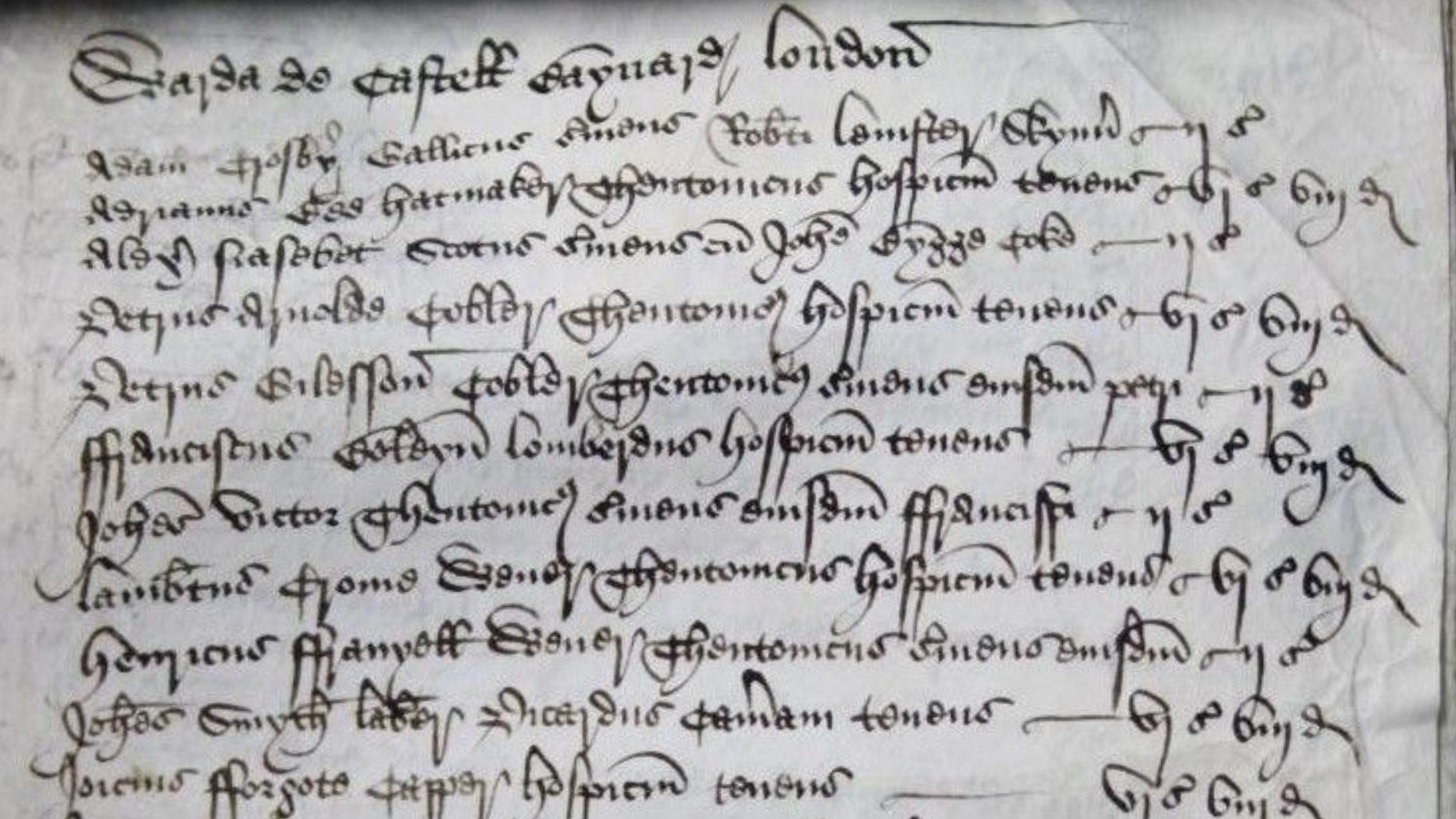

A fragment of the Alien Subsidy tax lists for the London wards of Castle Baynard and Farringdon Without in 1483. The National Archives, E 179/242/25, m. 16. This tax was collected from everyone who lived in England but was born abroad. The photograph shows the name of the taxpayers, their occupation and their origin.

A fragment of the Alien Subsidy tax lists for the London wards of Castle Baynard and Farringdon Without in 1483. The National Archives, E 179/242/25, m. 16. This tax was collected from everyone who lived in England but was born abroad. The photograph shows the name of the taxpayers, their occupation and their origin.

Economic success promoted political career but also held it back

The only exceptions to this picture were places where English manufacturers were in economic trouble, including London. Lambert: “In some English cities, local merchants and craftsmen suffered from competition from their alien counterparts. They tried to thwart the more successful migrants, sometimes even physically attacking them.” In their attempt to eliminate their immigrant competitors, they also tried to exclude them politically, for example by denying them the right to stand for political office. “However, the number of places where such a thing happened was extremely limited,” Lambert says. “In general, English city politics during this period was remarkably open to newcomers from abroad.”

The original article is available here.